When

it comes to the Civil War in Indian Territory, historians tend to gloss over or

sometimes ignore the events between the Battle of Pea Ridge and the expedition

of summer 1863. However there were many important developments in the territory

during this period that saw momentum shift continually between the Union and

Confederacy and also escalated various forms of violence within the territory.

These events were also influenced by actions across the border in Missouri and

Arkansas. This series covers three periods of Indian Territory, 1862. The first

section covers the plight of Indian refugees in Kansas and the attempt to

establish a strong Union presence in the summer of 1862. The second centers

around the Battle of Newtonia, which was actually in Missouri, but saw heavy

involvement by Indian troops. The third covers the Federal incursion of late

1862, which finally established a strong Union presence in the territory.

The Refugee

Crisis

In the early days of the war in 1861, the Confederacy obtained alliances with most of the Indian peoples in Indian Territory. The issue was that, like the borderlands to the east, the inhabitants were deeply divided as to what course they should take. While most of the leadership sided with the Confederacy (they shared many cultural traits such as slavery), many favored the Union and others did not want to get involved at all. In a series of battles, Confederate Indians, backed by white troops from neighboring states, assaulted pro-Union Indians. Thousands of refugees escaped to Kansas in the midst of winter. The suffering exiles wanted to get back to their homes. Many within the Federal government and army were keen on seeing that happen.

At

the end of 1861 President Abraham Lincoln created the Department of Kansas. He

angered and alienated firebrand and leading Kansas jayhawker James M. Lane by

choosing Major General David H. Hunter instead. Lane personally went to

Washington and pressured Lincoln to give him authority over the department.

Lincoln refused, but attempted to salve his feelings by giving the go ahead for

a longtime scheme of the Jayhawkers. This was the invasion of Texas from the

North. Naturally, to get to the Lone Star State they would have to cleave their

way through Indian Territory.[1]

Lane

was still not satisfied and continued to raise trouble. Lincoln finally moved

Hunter over to a coastal department along the Lower Atlantic Seaboard, but

still would not give Lane the command. He was simply too controversial a figure

after his many violent raids into Missouri. Still, Lincoln practically handed

him power by allowing him to choose the Departmental commander himself. Lane

chose one of his allies, Brigadier General James G. Blunt. Blunt was an

aggressive officer and always spoiled for a fight. This made him very popular

among the rough frontiersmen that would make up his various commands across the

war.[2]

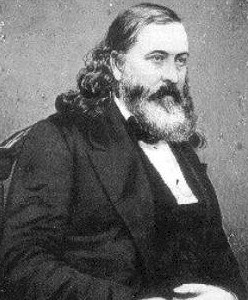

|

| James G. Blunt was a physician who first experienced violence as an Abolitionist in Bleeding Kansas. |

Lane and Blunt’s plans of a southward invasion lined up with the plight of Unionist Indians. These refugees resided in southern Kansas, in crowded camps where sickness and starvation ran rampant. The winter of early 1862 was particularly brutal. The Federal government and Department of Kansas were not prepared to handle the large influx of needy people. Thus many slept on the cold, hard ground, with prairie grass “their only protection from the snow. For shelter they had to strap rags and other forms of cloth across sticks. Many a toe was frozen and lost. In these crowded conditions food also got cross-contaminated, so that the choice became starvation or disease. The Army tried to help out, but their donations always fell severely short. They stopped altogether in mid-February.[3]

The

plan was to return these refugees to Indian Territory, where hopefully they

would be better fed and clothed. Then they would no longer be a serious burden

on Kansas or the Federal government. Seeing a potential source of new recruits,

as well as needing a force to protect the returning exiles, Blunt sought and

received authorization to raise Indian regiments. James Lane and several

officials continually promised the refugees that they would return them to

their homes, and talked up the formation of the regiments. However, weeks

passed without any development. Indians were confused as to why the Federal

Government, supposedly so powerful, could be so slow in following up on its

promises.

As

it turned out several ranking military figures, including General Henry

Halleck, were disinterested in organizing Indian regiments and dithered on

relaying orders from Washington that would have set in motion the organization

and armament of these units. It took pressure from Washington, through General

Lorenzo Thomas, to finally get the regiments organized and equipped. The

officers in Kansas got to work. Fort Leavenworth held a large stockpile of

Indian Rifles, long-barreled rifles that fired round bullets. The Indians

actually tended to prefer them over the regular Army muskets. The Indian Rifles

were good for fighting amidst woods and timber, where they could rest the

barrel against a tree or log.[4]

|

| Indian Home Guard soldiers (illustration from an Osprey Military book) |

The Confederates had recently lost the

Battle of Pea Ridge. This defeat enabled Union forces to gain a strong foothold

in Arkansas. Worse, Major General Earl Van Dorn took almost all the white

troops east across the Mississippi. This dangerously exposed much of the

Trans-Mississippi to invasion. Following Pea Ridge and its strategic fallout,

General Albert Pike, commander of Indian forces and the one who had made the

treaties with their chiefs, anticipated a Federal invasion. He believed he

lacked the manpower to successfully challenge a Union thrust, and thus centered

his line closer to the Texas border. From there he hoped to harry any enemy

incursions and force them to stretch out their supply lines.[5]

Albert Pike (above left) was content to sit still at

Fort McCulloch in the Choctaw Nation. In fact he openly defied Arkansan General

Thomas Hindman, the new commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department. Hindman had

just learned, to his shock, that he practically had no army with which to defend

his home state. He thus implored Pike to send all his remaining white troops to

Little Rock, Arkansas, and move his Indians near the border to block raids from

Kansas. Pike felt that this was a violation of the treaties he had made, which stated

that the Indians would not be obligated to fight outside their own lands.

Colonel John Drew, a Cherokee and relative of President John Ross, also stayed

still, interested only in protecting his people against invasion. For the

moment it was only Colonel Stand Watie, another Cherokee, and newly assigned

Colonel Douglas H. Cooper (above right), who were doing any real fighting.[6]

John Ross, President of the Cherokee Nation,

was likewise frustrated with the Confederacy, and also at Pike. Stand Watie’s

scouts brought back the sinister report that a Federal buildup was occurring across

the Kansas border. An invasion at this time would be dreadful. The Indian

troops were poorly clothed and still waiting for their pay from the Confederate

government. There were almost no white troops to bolster their weak defenses,

and Ross was angry with Pike for centering what he had in the southern part of

the territory instead of protecting the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokees resided

in the northeastern part of the territory, bordering Union Kansas and the

warzones in Arkansas and Missouri. If there was any invasion, it would come

through here.[7]

Douglas H. Cooper a former Federal

Indian Agent, had assumed command over the Indian regiments in the Territory.

So far he had no major battles under his belt. He had Stand Watie and his

Cherokees maintain a presence in the northeastern corner of his command. Watie

had several small skirmishes with the Federals. On May 31, at Neosho, Missouri,

he and a Missouri State Guard contingent under Colonel John Coffee surprised a

camp of Union militia cavalry. The militia tried to make a stand, but quickly

fell apart and ran. Coffee’s mounted men chased them down and killed 10 before

breaking off. Later on June 8, Colonel Charles Doubleday and his 2nd

Ohio Cavalry attempted to disperse a gathering of Confederates at Cowskin

Prairie near Grand River. Once again Watie was with Colonel Coffee. Doubleday

sent a battalion of cavalry to flank Watie’s camp from the south while he moved

his artillery and infantry through the woods to hammer him from the north. At

night, the Federal artillery bombarded the camp. Doubleday’s plan was to send

the Indians running into a trap. However, Watie and Coffee skillfully navigated

the woods and slipped away. While they suffered no losses (neither did the

Federals), they did lose hundreds of horses and cattle.[8]

Doubleday’s

foray was more than just a one-off assault. He had been scouting out the area

as the Indian Expedition came together. Colonel William Weer, the former Attorney General of Kansas, was to command this mix of

white and Indian troops. Doubleday advised him to move quickly before the

Confederates in the area united their forces. Weer was eager to heed his words

and started the expedition forward. A pair of Indian Agents came along to

analyze the situation in the territory, report their findings, and see how they

could help the Indians (likely with an eye to making them supporters of the

Union). A Reverend Evan Jones also came along with a confidential message for

Cherokee leader John Ross.[9]

The first Federal incursion into Indian Territory was on the way, and

Confederate resistance was divided and in some cases unaware of what was

coming.

Locust Grove

Weer learned that Watie was at Spavinaw Creek, with the other Confederates 20 miles south at Locust Grove. Weer planned to hit the separated Watie first and then take the rest of the enemy. The 6th Kansas Cavalry rode ahead to the creek. When they got there Watie had already gone south.[10] The Confederate Indians were soon aware of the Federal invasion. Small groups of them would appear along the line of march, prompting brief chases. One early history by a Union veteran claimed that they almost captured Watie “several times.” The pursuers were said to be so close that they would empty their revolvers at the number one Confederate Indian. At one point they came upon a house where he was dining with a friend. Alerted by his pickets, Watie and his small escort mounted their horses and sped into the hills. With the Kansans right on his tail, Watie selected two companies and halt the chase with an ambush. The foremost Federals rode right into a hail of bullets from pistols and shotguns. Though on the run, Watie’s inability to die or be captured added to his notoriety. The next day, during a thunderstorm, a private in the 9th Kansas Cavalry thought he could hear the Indian’s laughter amid the crackling booms.[11]

|

| Trading Card of Stand Watie |

Unable to bag Watie, Weer was still determined to get to Locust Grove and the Confederate gathering there. He gathered several detachments and headed there in a night march. His force included men from the 1st Indian, 9th Kansas Cavalry, 10th Kansas Infantry, and Allen’s Battery. In total he had between 200 and 300 men.[12] Locust Grove was named for the local post office. It is situated 2 miles east of Grand River and 30 miles north of Tahlequah. The terrain, at least at the time of the battle, was of a “bushy nature” with many trees. There, Colonel James Clarkson, a former officer in the Missouri State Guard, commanded about 300 mostly Missourian men. They guarded an encampment with wagons.[13]

After

“traveling rapidly all night,” the 10th Kansas reached their target

at sunrise. An early history stated that Weer’s scouts arranged for him to

arrive at just this moment, as it would enable him to surprise Clarkson’s men while

still having enough light to conduct a battle.[14]

After surprising and capturing some of the enemy pickets, the Federals

surrounded the encampment, where most of the men were still sleeping. They

opened fire and Clarkson’s men ran about in confusion, still in their night

clothes. They made for an escape. A good number got out before the Federals

tightened their coils and forced them into a fight.[15]

Weer

deployed his battery with the 10th Kansas as guard. He advanced his

other two detachments (1st Indian and 9th Kansas Cavalry).

Formations did not work here as the fighting occurred amidst bushes and trees.

“…Each participant was thrown more or less on his individual resources.” The

Union guns stayed silent. Weer reported that the battery section “was only

prevented from paying its respects to the enemy from fear of destroying our own

men, who were engaged with the enemy in the woods in scattered parties.” Amidst

the fray, one soldier in the 9th Kansas accidentally shot and killed

an Assistant Surgeon Holleday from the 1st Indian. Seeing their

situation as hopeless, numerous Confederates surrendered. Colonel Clarkson was

among them.[16]

The

battle was so brief that only the 1st Indian Home Guard and 9th

Kansas got to engage. The 10th Kansas and artillerymen had really

wanted to pitch in and were only kept in place “with difficulty.” Weer counted

30 Confederates killed (he built it up to 100 in his follow-up report) and 100

captured, along with “their entire baggage wagons mules, guns, ammunition,

tents, &c.” The wagons primarily held ammunition, clothes, food, and salt.

In theatre further east this would be an inconvenient occurrence. Out here in

Indian Territory it was a significant blow. Weer counted two of his men killed,

1 from the 1st Indian and 1 from the 9th Kansas. The next

day was of course the 4th of July. The victors headed back to Cabin

Creek and celebrated the holiday by dividing the captured clothes and food

among the accompanying refugees.[17]

The Expedition

Stalls

After

soaking in his victory, Weer advanced his army to Flat Rock. From there they

proceeded south to Fort Gibson. On July 14 the 6th Kansas Cavalry

under Major William Campbell pushed away the pickets there. From a handful of

prisoners they heard that the Confederates were concentrating south of the

Arkansas River. The next day Campbell and Weer entered the fort itself. The 6th

Kansas continued south to the Arkansas River to investigate the concentration.

There they had a near-bloodless skirmish with Confederates on the other side.[18].

Amidst

the successes of his force, Weer found himself having to control his Indian

soldiers. They wanted vengeance for what had happened to them and their

families over the previous winter. Weer said he had “great difficulty in

restraining the Indians with me from exterminating the rebels. A good deal of

property has been destroyed in spite of all my efforts.” Weer was also

overwhelmed by the sudden effects of his victory. He had just rapidly advanced

into the Cherokee Nation without any further reinforcements, and also had to

contend with the area’s unique political situation.[19]

|

| President/Chief John Ross |

Weer detached a company of the 6th Kansas Cavalry and 50 Cherokees, under Captain H.S. Greeno, to Tahlequah, the capital of the Cherokee Nation. Greeno was to find President John Ross and get him to break off his alliance with the Confederacy. He encountered no resistance and arrived at the chief’s home. He called upon Ross to come to Weer’s camp and discuss the future course of the Cherokees. He wanted him to renounce his peoples’ allegiance to the Confederacy. Ross felt himself too old and ill to come out. Greeno accommodated him. Ross would stay at his home until proper Federal authorities arrived. His official status was as prisoner-of-war.

This

was to prevent him from backing a proclamation from Colonel Douglas Cooper.

Cooper was calling for recruits to repel a Federal invasion. They were to

gather at Fort Davis south of the Arkansas River. 500 Arkansans were reported to

have crossed into the territory already. Ross was actually welcoming of the

return of the Union to Indian Territory, but felt that he could not break his

word to the Confederacy. Greeno reported that, “The Chief seems very much

concerned about the situation of the people of his nation, and anxious that the

United States Government should send sufficient force here to protect them from

lawless bands that are daily threatening them, committing robberies and

murders. He is quite apprehensive of his own personal safety and the safety of

his family.”[20]

The

news of Weer’s advance as well as the crushing defeat at Locust Grove had a

tremendous effect on the leading Cherokee men. A group of them came with Greeno

back to Weer. As it happened they were officers of Colonel John Drew’s Pin

Cherokee regiment. These men had been much more reluctant than Watie’s faction

to ally with the Confederacy and saw an opportunity to switch sides. Greeno in

fact delivered a speech in which he listed the long string of Confederate defeats

throughout the first half of 1862. He promised that the U.S. government was not

vengeful and would welcome Cherokee support. When Greeno headed back to Weer,

he brought along 200 new Cherokee recruits.[21]

Weer

and his force settled in at Flat Rock, taking in further Cherokee recruits.

Weer organized these into a third Indian regiment and placed it under the

command of Colonel William Phillips (who had been an antislavery reporter in

Kansas). Colonel Furnas of the First Indian Regiment became commander of a now

three-regiment brigade. Furnas found his command frustrating, as many of the

Indians did not stick to the white man’s sense of discipline. At one point 180

Osages left to hunt buffalo. Furnas sent out a detachment to bring them back,

but Watie had gotten to them first. The Cherokees dispersed them, capturing 14.

The

Federals waited for a promised supply train from Fort Scott. After two weeks it

still had not shown up, and supplies were running low. Worse, the weather had

grown oppressively hot and dry, to the point that prairie grass easily caught

on fire. Weer seemed to lose his mind (the accusation was that he got drunk in

these desperate conditions), refusing to either advance further or withdraw.

Fearing what would happen if they continued to linger, the regimental

commanders gathered together. They resolved that, as they were 160 miles from

their base of supply and the wagons were not arriving, they would arrest

Colonel Weer and put Colonel Frederick Salomon, a veteran Prussian officer who

had led German troops in a couple of the 1861 Missouri battles, in charge. They

headed back north, under the agreement they would stop if they happened to come

upon the supply train.[22]

Blunt

was furious when he heard that Salomon and Weer had abandoned their position.

Despite this, both colonels received promotion to brigade command in Blunt’s

own newly formed division of the Army of the Frontier. Perhaps he realized that

their position had been untenable for lack of further support. Still, they had

left a much reduced force to face a resurgent Confederate Indian force.[23]

A Failed

Foothold

The

Federal foothold in Indian Territory was not as strong as hoped. One reason of

course was the failure of Weer to advance for lack of supplies. Another reason

came from further east in Missouri. Though official Confederate forces had been

pushed out of the state, numerous guerilla leaders led swift and usually

mounted bands against Federal forces. In general they proved much more

effective at stymieing the Union war effort in the Trans-Mississippi than the

Confederate Army. Confederate cavalry such as those under General Jo Shelby

also started to make raids against Federals in Missouri, as well as Arkansas.

Brigadier General John Schofield found the problem overwhelming and had to call

on Blunt for more men to suppress these activities. This left only the Union

Indian Home Brigade and a token force of Kansas artillerymen to defend refugees

and civilians.[24]

John

Ross also left the territory, along with his family, political allies, and

wagons laden with the Cherokee governmental archives. The president’s departure

North caused more problems. His government had been a somewhat moderating

force. Once he and his associates had departed, his metaphorical lid popped off

a jar of potential violence within the Cherokee Nation. Drew’s Union-leaning

Cherokees went to war with the Confederate faction. Both sides ransacked and

burned homes, destroyed crops and livestock, and murdered each other as well.[25]

Drew’s

faction briefly gained the upper hand at a skirmish on July 27. William

Phillips’ 3rd Indian Home Guard (the Cherokee regiment) advanced

along three roads towards a fork at Bayou Bernard. One column, under Lieutenant

Haneway, bumped into Watie’s men near a hill (Park Hill). Haneway’s men fired a

little and then fell back along the Park Hill Road. The Confederates pushed

into the Home Guard’s center. The Union Indians blasted them and they retreated

on horseback, “in great confusion” according to Colonel Phillips. The Federals

listed just one man severely wounded and claimed to have found 32 dead foes,

among them a lieutenant-colonel. They also took about 25 prisoners.[26]

|

| Colonel William Phillips |

Despite their victory, the Union Indians were about out of rations. Phillips distributed the last of his bread boxes. He was reluctant to withdraw and asked for rations to be sent to him. Phillips advanced his three regiments to the west side of the Grand River, hoping to link up with Major George Foreman. Foreman had already fallen back north. Phillips then attempted to cut off McIntosh’s Confederate Creeks between the Verdigris and Arkansas Rivers. Once again he was too late, as McIntosh went south to join the rest of the Confederates at Fort Davis. A detachment went for Creek Agency Ford, where they found earthworks, but only a tiny token force which hastily fled. Phillips stayed along the Arkansas River. However, the Confederates would not engage him and he was still dangerously low on food, so he fell back north again.[27] Morale fell among the Union Indians. The 1st regiment grew uncontrollable while the most of the 2nd deserted. Unable to stay and with no chance to inflict another blow, the Indian Home Guard also turned back towards Kansas, taking along captured cattle. Pro-Union civilians joined the column, knowing what might befall them without army protection.[28]

Thus,

without winning any major battle, the Confederates regained control of Indian

Territory. Unfortunately this did not end the violence within the Cherokee

Nation, but made it more one-sided. The pro-Confederates wreaked vengeance on

any Union ally left in the territory, as well as white missionaries who

happened to be Abolitionists. They accused the Abolitionists of stirring the

Pins up against the Confederacy and thus dividing their people. About 2,000

more Indians fled into Kansas’ crowded refugee camps. With all political

opponents out of the way, Stand Watie assumed command of the Cherokee Nation,

though he still fought as a colonel.[29]

General Blunt, commanding a division in the now organized Army of the Frontier,

hoped to personally give Indian Territory another try. In August he was ready

to lead his troops in and this time establish a more permanent foothold, but

his superiors reined him in thanks to developments in the east.[30]

There

was also a change in leadership within Indian Territory. Albert Pike, who had

been critical in fostering an alliance with the nations within the region, had

been falling into the background since Pea Ridge. When General Thomas Hindman

took control of the war effort in Arkansas, Missouri, and Indian Territory,

Pike felt that he was just as inconsiderate of the needs of the Indians as any of

his predecessors. He was upset that Hindman kept requisitioning clothes and

supplies reserved for his charges. Pike resigned his commission and left on

July 31. Hindman supported Douglas Cooper, a former Indian Agent, as his

replacement, though he did express his desire to have fellow Arkansan and

friend General Patrick Cleburne take the post. Cooper had served as a

regimental commander in the first year of the war and was by the summer

commanded forces north of the Arkansas River. He was much more willing to go

along with Hindman’s directives and joined a congregating Confederate army in

Arkansas.[31]

Both

sides thus put the war in Indian Territory on hold. Indians on both sides would

instead participate in a battle in southwestern Missouri.

Next

when I continue this series: Confederates and Choctaw allies enter Missouri to

prepare the way for a major offensive. They clash with Federals under Colonel

Frederick Salomon at a town called Newtonia.

Sources

Abel, Annie

Heloise. The American Indian in the Civil

War, 1862-1865. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

“Battle of

Locust Grove.” https://web.archive.org/web/20150923204423/http://www.civilwar-album.com/indian/locustgrove1.htm.

Britton, Wiley. The Union Indian Brigade in the Civil War.

Kansas City: F. Hudson Publishing Co., 1922.

Cottrell, Steve.

Civil War in the Indian Territory.

Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company, 1995.

Duncan, Robert. Reluctant General: The Life and Times of

Albert Pike. New York: Dutton, 1961.

“General Blunt’s

Account of His Civil War Experiences.” Kansas

Historical Society Vol. 1 No. 3 (May 1932): 211-265.

Josephy, Alvin M. The Civil War in the American West.

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991.

Knight, Wilfred.

Red Fox: Stand Watie’s Civil War Years in

Indian Territory. Glendale: A.H. Clark Co., 1988.

Monaghan, Jay. The Civil War on the Western Border,

1854-1865. Boston: First Bison Book Publishing, 1955.

United States. The War of

the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies Vol. XIII.

Washington D.C. 1898.

Wood, Larry. The Two Civil War Battles of Newtonia. Hoopla Edition, History Press, 2010.

[1] Alvin M. Josephy, The Civil War in the American West, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), 351.

[2] Josephy, American West, 351.

[3] Josephy, American West, 354; Annie Heloise Abel, The American Indian in the Civil War,

1862-1865, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992), 82-83.

[4] Josephy, American West, 354; Wiley Britton, The Union Indian Brigade in the Civil War, (Kansas City: F. Hudson

Publishing Co., 1922), 61; Abel, American

Indian, 92, 95, 106-110.

[5] Steve Cottrell,

Civil War in the Indian Territory, (Gretna:

Pelican Publishing Company, 1995), 42.

[6] Abel, American Indian, 110-112, 128-129.

[7] Robert Duncan, Reluctant General: The Life and Times of

Albert Pike, (New York: Dutton, 1961), 239-240.

[8] United States, The War of

the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies Vol. XIII, (Washington

D.C. 1898), 62, 102; Larry Wood, The Two Civil War Battles of Newtonia, (Hoopla Edition, History Press, 2010), 25; Wilfred

Knight, Red Fox: Stand Watie’s Civil War

Years in Indian Territory, (Glendale: A.H. Clark Co., 1988), 111-112;

Cottrell, Indian Territory, 44.

[9] Abel, American Indian, 119-123.

[10] Knight, Red Fox, 114.

[11] Knight, Red Fox, 114-115; Britton, Indian Brigade, 65.

[12] OR XIII, 137.

[13] OR XIII, 137; Britton, Indian Brigade, 65-66.

[14] OR XIII, 137; Britton, Indian Brigade, 65.

[15] Britton, Indian Brigade, 65.

[16] OR XIII, 137-138.

[17] OR XIII, 137;

“Battle of Locust Grove,” https://web.archive.org/web/20150923204423/http://www.civil-waralbum.com/indian/locustgrove1.htm;

Britton, Indian Brigade, 66.

[18] “Battle of

Locust Grove,” https://web.archive.org/web/20150923204423/http://www.civilwaralbum.com/in-dian/locustgrove1.htm;

OR XIII, 160-161.

[19] OR XIII, 138.

[20] Britton, Indian Brigade, 67-69; OR XIII, 160-162.

[21] Britton, Indian Brigade, 68-72; OR XIII, 162.

[22] Britton, Indian Brigade, 66-67; Knight, Red

Fox, 119; Jay Monaghan, The Civil War

on the Western Border, 1854-1865, (Boston: First Bison Book Publishing,

1955), 253; Cottrell, Indian Territory,

50.

[23] Cottrell, Indian Territory, 51.

[24] Josephy, American West, 358; Cottrell, Indian

Territory, 51.

[25] Monaghan, Western Border, 253; Josephy, American

West, 358-359.

[26] OR XIII, 181-182; Josephy, American West, 359.

[27] OR XIII, 182-184.

[28] OR XIII, 184; Abel, American Indian, 145; Josephy, American West, 359.

[29] Josephy, American West, 359.

[30] Abel, American Indian, 196.

[31]Josephy, American West, 360-361; OR XIII, 51;

Knight, Red Fox, 112; Monaghan, Western Border, 256-257.

No comments:

Post a Comment