In the last part we looked at the origins of the Kingdom of Dahomey, and how it settled into its role as a regional slave-trading power. Here we cover the 18th Century, when the slave trade went largely unquestioned by Europe and provided Dahomey with a wide range of customers. However, it was not as profitable as the African rulers may have hoped.

|

| An 18th Century army procession, led by (possibly) a king with a feathered hat. Note all of the umbrellas. Umbrellas were a status symbol in Dahomey and could be quite colorful in their design. |

Chapter II: The Tegbesu Dynasty

Tegbesu

Unlike his father, Tegbesu was very accommodating to European traders. He helped them maintain their forts and trading posts. In one incident 1743 he had a Portuguese fort blown up to display his power over the port of Igelefe. The Portuguese was harboring a Hueda leader. The Hueda were still trying to regain control of Ouidah and throw off their dependent status to Dahomey. Often suspecting the Europeans of siding with their enemy, the Dahomeans would sometimes launch attacks on European forts. On July 21, 1743, they targeted the Portuguese fort. At some point the fort’s powder magazine detonated and the Dahomeans were able to enter and kill many of its inhabitants in their search for the Hueda leader. After this the Europeans never backed the Hueda in their power plays, though the former rulers of Ouidah would make further attempts into the 1770s with backing from Little Popo (in present day Togo).

Since

the Portuguese were customers, Tegbesu proceeded to help rebuild their fort for

free. He also sought to centralize the slave trade through Ouidah, as it had

always been a major link for trade. With a more powerful government than the

earlier Huffon, he succeeded. To Tegbesu’s frustration, however, the Portuguese

instituted a law in which their ships must take turns going to Ouidah. As a

result impatient captains patronized other ports along the West African coast,

depriving the Dahomey of further profits.

Tegbesu

also tried to run a peaceful slave trade, buying slaves from Oyo and reselling

them to the Europeans. This policy caused a shortage. By the 1770s the American

Revolutionary War and falling prices on slaves in the West Indies made slave

trading with Dahomey by the British and French unprofitable. Dahomey’s

monoecomic reliance on slavery resulted in a depression, starting in 1767. It

could not maintain a high enough supply of slaves. Even then, not enough

European ships came to haul all of their captives across the Atlantic. The

Little Popo and Hueda also cut off beach access several times in the early

1770s. This was the great problem for Dahomey. It was so focused on the

profitable slave trade that it left itself open to massive fluctuations in the

market. This would become a greater problem once abolitionist movements gained

steam in the western world, Dahomey’s best customer.

|

| "Public Procession of the King's Women" from Archibald Dazel's History of Dahomy |

Kpengla

In

1774 Tegbesu died. Kpengla assumed power and reversed his father’s slave trade

policies. He was determined to become a chief player in the Trans-Atlantic Slave

Trade. From now on Dahomey would raid its neighbors (excepting the Oyo of

course) in an effort to procure human chattel. Since Dahomey had been unable to

procure proper firearms for years, these raids ended in disaster. On most

occasions they were routed without captives or completely wiped out. Buying

slaves from kingdoms in the interior did not help much as prices had risen on

them. In turn this meant they had to raise prices when selling to the Europeans

or sell for less profit. Kpengla also struggled to attract his desired

customers. He attempted to fix the prices for slaves from the interior so he

could make a profit, but this only drove interior slave sellers to send their

human goods elsewhere. He further tried to get the Europeans to go to Jakin, which

he was trying to revive as his personal and thus monopolized trading site. They

preferred Ouidah, where slaves were sold by independent businessmen.

Kpengla

then struck upon his most vile scheme yet. He ordered all non-Dahomeans (except

the Oyo) in Igelefe rounded up. He accused them of disclosing secrets to his

enemies. This was of course a complete fiction, but now he had a sizeable

number of slaves to sell at Jakin. He also forced independent slave traders to

sell him two-thirds of their slaves at discounted prices. Still the slave ships

did not come in desired numbers, preferring the Portuguese trading post at

Porto Novo outside Dahomey. Kpengla’s rein was not barren of successes. His

great victory in this period was the final defeat of Hueda resistance. After a

failure to establish peace with British intermediaries, Kpengla ordered an

offensive in 1774. Victory in 1775 broke Hueda military power, permanently

ending its raids against Dahomey. The Little Popo would remain an enemy for 20

more years.

Regardless

of Kpengla’s triumph, the economy still floundered in the 1770s, and at a time

when the Oyo stepped up their tribute fees. Kpengla barely staved off invasion while

he found ways to satisfy Oyo’s demands. Salvation finally came in the early

1780s, as the American Revolutionary War wound down. The British and other formerly

distracted European powers now frequented all West African ports. At the same

time the Oyo Empire suffered a shock as internal quarrels escalated into

violence and successful independence wars. Kpengla stepped into the situation,

offering to use Dahomey as a middleman in the slave trade between the Europeans

and Oyo in exchange for helping suppress the Oyo king’s enemies. The Oyo

shortly broke their end of the bargain and Kpengla banned all slave trading

with them. He then monopolized Dahomey’s slave trade under his command. Able to

procure good firearms, he resumed slave raids on his neighbors.

One

of these wars was against Epe in 1778. Swampy terrain along the coast greatly

obstructed Dahomean advances. Dahomey was not known for a navy and it had to

enlist the aid of its subject Allada to transport troops to more favorable

terrain. Another Dahomean force marched overland. The land force beat back the

Epe, but were halted when they came across a fortified swamp. The waterborne

force landed, but the Epe there struck first, capturing the boats, boarding

them, and routing the remaining Allada force. Led by the king, these Epe

warriors were able to turn into the rear of the main Dahomean land army. Though

they retreated, the invaders made off with much plunder and captives.

One

notable raid occurred in 1781 when Oyo demanded a larger tribute of women. Kpengla

was loathe to hand over more of his own women, so he commanded his soldiers to raid

Agouna and take its women. The raid was repulsed. Determined to succeed, Kpengla

personally led 800 armed women from his harem of “wives” against Agouna and

scored a victory. 1,800 people of Agouna were enslaved, many of the women of

course going to Oyo. The success of the raids in general, however, was mixed.

As

usual, many of the captives were destined for human sacrifice. Archibald Dazel,

the Scottish head of Britain’s post at Ouidah, recalled one time when Kpengla

paraded his captives before him. Some were strong, but many “were much

emaciated, and appeared to be sickly. Dazel had no interest in purchasing them,

so Kpengla said, “Since that is the case, I shall put them to death.” Dazel

tried to change his mind, arguing they could be put to work boiling salt, as

they came from a region rich in the resource. The king could not be moved

however, explaining “it would be setting a bad example, and keeping people I the

country, who might hold seditious language that his was a peculiar government, and

that these strangers might prejudice his people against it, and infect them

with sentiments incompatible with it.”

|

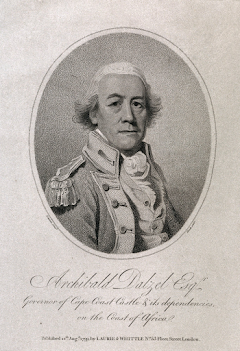

| Archibald Dazel (Johann Eckstein illustration from 1799). Dalzel's History of Dahomy provides several images in this post. |

Dazel also had a more famous exchange with the ruler. He and various other Europeans dined with the king. They talked of how the Dahomean wars were carried out to provide slaves for their ships. Kpengla disagreed. “Your countrymen therefore, who allege that we go to war for the purpose of supplying your ships with slaves, are greatly mistaken…no Dahomean man ever embarked in war merely for the sake of procuring wherewithal to purchase your commodities.” The king went on to remind his guests that he killed as much as sold his prisoners, especially in ritualistic human sacrifice. His general argument was that the sale of human life was simply a way to make money off the wars they would naturally fight anyways. “You Englishmen, for instance, as I have been informed, are surrounded by the ocean, and, by this situation, seem intended to hold communication with the whole world, which you do my means of your ships; whilst we Dahomans, being placed on a large continent, and hemmed in amidst a variety of other peoples…are obliged, by the sharpness of our swords, to defend ourselves from their incursions, and punish the depredations they make on us.”

|

| The 1793 illustration "Victims for Sacrifice" |

Kpengla’s reasoning has some merit, as the various African kingdoms were always fighting for land and non-European slavery, but the king ignores several moments in Dahomey history were raids were conducted solely to feed international trade at Ouidah. For Archibald Dazel’s part, the Scotsman argued that by buying slaves the Europeans were rescuing thousands of Africans from human sacrifice. In fact his choice to include the king’s speech might have been to justify this line of thought. If the Dahomeans were going to wage constant wars anyways, why should Britain and other foreign traders at least save thousands from a horrendous death (never mind the horrendous servitude awaiting many in the Americas)? No matter how insidious their actions, people of all cultures find it necessary to concoct a humane or rational reason. Kpengla died in 1789. While he never created a successful save trading empire on the level of more powerful West African kingdoms, Kpengla did manage to improve his country’s military situation.

Fall of the

Tegbesu Dynasty

Agonglo

ascended to the throne, inheriting his father’s problems. He started his reign

by lowering taxes, which had oppressed lower-class Dahomeans, and removing

unpopular restrictions on the nobles and traders. To attract more ships, he

removed tariffs and duties. As with his father’s time, however, his attempts to

raid his neighbors failed to produce human stock for his ports. In 1795 the

army finally scored a decisive victory against Little Popo, a major enemy,

though Agonglo’s aggressive actions did scare off some of his customers. In

this war the Popo chief, Agbamou, was killed, and Dahomey expanded its border

west.

This

victory, with its resultant human captives and extra territory, could only

partially compensate for an event the previous year. France had undergone

revolution, and the new regime promoted the goals of liberty and equality. The

euphoric French abolished the slave trade. French warships began to attack

slave ships along the African coast. Among their victims were the Portuguese

ships at Ouidah. Ouidah had gained a reputation as a safe port, and now it was

shattered. Seeking to restore relations with Portugal, Agonglo actually

considered baptism into the Catholic faith. This caused an uproar, and a Na

Wanjile, a woman at the palace, shot Agonglo dead on May 1, 1797. The resulting

war for the throne saw Adandozan, Agonglo’s second son, assume the throne on

May 5.

After

disposing of his political enemies, Adandozan launched slave raids against his

neighbors. As with other Tegbesu kings, his campaigns were often fruitless.

Desperate, he ordered an attack against Oyo’s port of Porto Novo in 1805 while

the Yoruba empire was distracted by an Islamic invasion from the north. His men

seized Portuguese traders, but the Oyo recovered from their land’s invasion and

cowed Adandozan into resuming the annual tributes. He at least had Portuguese

hostages and made an agreement to release them. In exchange the Portuguese were

to assist in development of mining and gun manufacturing in Dahomey. The

Portuguese were amenable enough to see their men released, but then refused to

agree to the discussed terms. If they were legitimately interested in Dahomey’s

requests, they could not follow through because Napoleon’s French forces had

just invaded their country. On the topic of Napoleon he reinstituted the slave

trade for the French, but this would be of limited benefit to Dahomean

suppliers.

The

next blow to the slaving business came in 1807, when Britain abolished the

slave trade. It shortly began to wield its influence within the anti-Napoleon

alliance to pressure the reduction of Portuguese slave trading. Unlike his

predecessors, Adandozan sought an alternative to the slave trade. In 1808 he

sought to reorient his economy to agricultural goods. Sadly this step away from

selling human lives was thwarted by famine, disease, and then heavy rains that

destroyed half the houses in Igelefe. In the midst of all these mounting

failures, the princes and ministers of Dahomey, as well as the Portuguese

trader Francisco Felix De Souza (to whom Adandozan owed a lot of money),

conspired to remove the king from his throne.

|

| Francisco Felix de Souza |

De Souza is the most visible European figure in Dahomey’s history. He was born in Bahia, a province of the Colony of Brazil. He first came to West Africa in 1792 and became a permanent resident around 1800. He struggled financially until he got a secretarial position at the Portuguese fort in Ouidah. In a couple years he rose to command of the fort, and with Brazil leaning towards independence and the various national bans on the slave trade, he transitioned into a private trader. Now, as a co-conspirator against Adandozan, he provided Europeans goods and arms. The goods could be used to buy support from more Dahomeans while the weapons of course would end up in their hands.

The

conspirators’ choice to replace Adandozan was Gezo, the king’s younger brother.

The story of Gezo’s rise to power is obscured by a heavy dose of propaganda, as

Gezo would begin a new line of kings. Tradition holds it that Agonglo had

actually named him his heir, but Adandozan took over as regent because he was

so young. Adandozan then clung to power, and Gezo and the Dahomey people had to

rise up to depose him. What is known for a fact is that in 1818 Gezo became

king with the help of Dahomey nobles and Portuguese traders. This was

accomplished after a palace coup, in which most of Adandozan’s own female

bodyguards sided with Gezo and enabled a quick victory. It is actually unclear

if Adandozan survived. Some report state that he lived until the 1860s, while

others assume he was executed alongside his sons and loyal followers.

The Tegbesu Dynasty had been a complete failure. King Agaja had given it a promising start, but was quickly undercut by Oyo invasion. The Oyo’s demands for tribute put further burdens on Dahomey’s economy. The kings had been almost single-minded in trying to fill the state coffers with the slave trade. Their raids and wars for slaves were generally failures, and the successes often occurred in alliances with other kingdoms. Adandozan had been the only one to try to break out of this mindset with an agricultural track, but a string of disasters had crushed it at the same time that momentum against slavery among European buyers began to emerge.

The

slave trade was now in a contested state. Dahomey still had plenty of

Portuguese and Brazilian buyers, but Britain would assume the role of moral

interloper. Despite these challenges, Gezo would usher in a surge in Dahomey

power.

Sources

"African

Eighteenth Century Warfare I." https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2015/08/23/african-eighteenth-century-warfare-i/

Akinjogbin,

I.A. Dahomey and it’s Neighbours:

1708-1818. Cambridge University Press, 1967.

Alagoa, E.H.

“Fon and Yoruba: the Niger Delta and the Cameroon” in General History of Africa Vol. V: Africa from the Sixteenth tot eh

Eighteenth Century. UNESCO, 1992: 434-452.

Alpern, Stanley

BB. Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women

Warriors of Dahomey. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Dalzel,

Archibald. The History of Dahomy, an Inland

Kingdom of Africa. London: T. Spilbury and Son, 1793.

Davidson, Basil

(ed.). The African Past: Chronicles from

Antiquity to Modern Times. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1964.

Herskovits,

Melville J. Dahomey: An Ancient West

African Kingdom. New York: J.J. Augustin, 1938.

“Kingdom of

Dahomey,” https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Kingdom_of_Dahomey

Law, Robin. Ouidah: The Social History of a West African

Slaving ‘Port,’ 1727-1892. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2004.

Ronen, Dov. Dahomey: Between Tradition and Modernity. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1975.

No comments:

Post a Comment