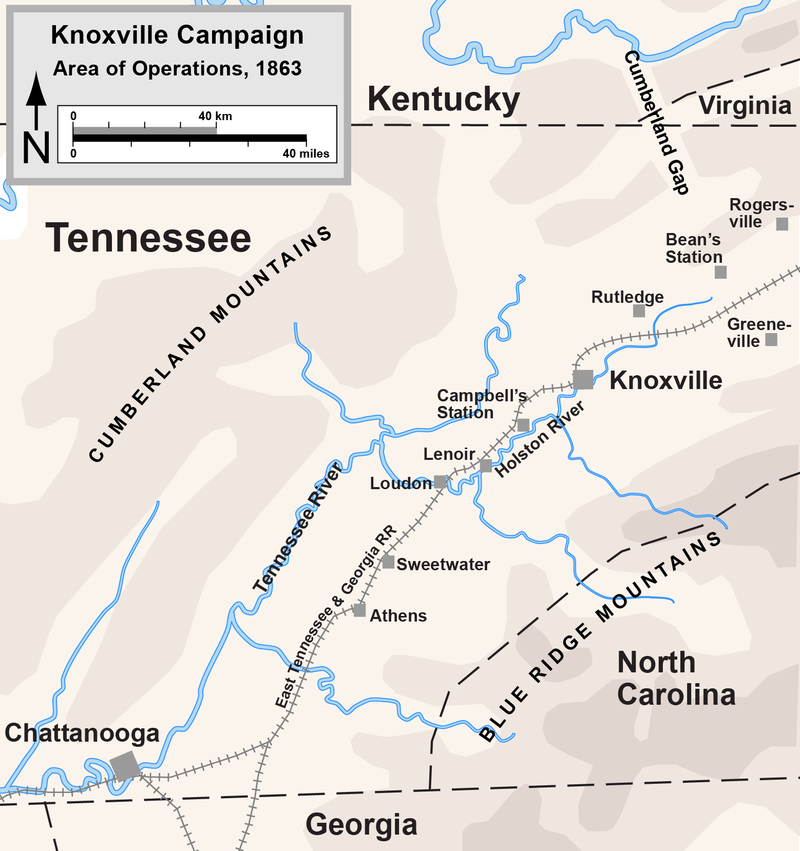

General James Longstreet is popularly portrayed as a voice of modern warfare in the Civil War. He has also become the voice of reason at the Battle of Gettysburg. If his superior General Robert E. Lee had listened to him and avoided frontal assaults than the Confederacy would have had a much better summer of 1863. One would think that, given independent command, Longstreet would excel. He did in fact have a good shot at independent command at the end of 1863. But rather than excelling, he performed poorly. Casual and even some avid Civil War buffs might be surprised to learn that he was defeated by Union General Ambrose Burnside, a man often regarded as just another incompetent general to lose to Lee in Virginia. So why did one of the most highly regarded Confederate generals do so poorly and to what extent should credit be given to Burnside? Here is a short look at the Knoxville Campaign, which was waged in November and December of 1863.

Longstreet Goes

West

Georgia-born James Longstreet was working as an army paymaster in New Mexico Territory when the war broke out. Resigning from the army, he soon led a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run. In 1862 he rose to become one of the South’s greatest generals and Lee’s most reliable subordinate. Commanding the First Corps, he did exemplary service up to the Battle of Gettysburg. While his criticisms of Lee’s risky offensive tactics were valid, his execution of these tactics were themselves mishandled. After the disaster at Gettysburg he looked west for both practical and personal reasons.

|

| General James Longstreet |

Caught in the middle of this was Longstreet. The Army of Northern Virginia under General Lee usually operated like a well-oiled machine, and when it did not the army was still an effective unit. Instead of bringing stability to the Army of Tennessee, Longstreet and his First Corps instead were themselves transformed by the chaotic state of affairs in the west. Longstreet himself harmed his reputation with Davis by joining the other generals against Bragg, while displaying obvious hopes that he would take Bragg’s place. When Davis asked Longstreet for his opinion of Bragg, Longstreet could only bear to give “an evasive answer.”[2] Longstreet’s battlefield performance plummeted. He halfheartedly challenged a Union move towards his lines, enabling the Federals to gain a strong foothold against Bragg’s lines.

Bragg

wanted to send Longstreet, along with Joseph Wheeler’s experienced cavalry force,

to secure East Tennessee. Davis and Lee both approved of this plan, partly

because it would put Longstreet closer to Virginia. If Lee was put in a

difficult situation, then Longstreet could come to his aid. Many contemporary

sources as well as historians have accused Bragg of simply trying to get rid of

a troublesome subordinate, at the expense of the strained Confederate lines

south of Chattanooga. He even wrote to Davis that Longstreet’s departure was “a

great relief for me.”[3]

Longstreet thus had a chance to prove himself in independent command, though

under less than stellar circumstances. His enemy was the Army of the Ohio,

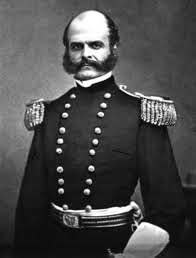

under General Ambrose E. Burnside.

A Chance at

Redemption

|

| Ambrose Burnside |

Though

his arrests and censorship against Copperheads created some controversy,

Burnside did start to rebuild his reputation in battling the guerillas. In

mid-1863 he was finally given another major military operation. He was to

advance into East Tennessee. East Tennessee had long been in the hearts and

minds of President Abraham Lincoln and administration. Slavery was not as

prevalent in this part of the state, and a considerable number of civilians

wished to stay in the Union. Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s future vice-president,

came from this region and was the only senator from a seceded state to remain

loyal to the Union. Lincoln long wished for the liberation of the Unionists

from Confederate rule, but a campaign for this task had failed to materialize.

Generals saw it as a low priority. Its difficult mountainous terrain and lack

of transportation routes rendered it unfeasible as an invasion route or military

target. While Union forces focused elsewhere, pro-Unionist guerillas and

activists were suppressed by the Confederate government, many of them hanged.[4]

Burnside

had his hands full operating in Kentucky, fighting off Rebel raids and ensuring

Kentucky’s 1863 elections went off smoothly (in other words, that the

pro-Unionist vote had its way). Burnside still viewed Kentucky as under threat

and only reluctantly complied with Army Chief of Staff Halleck’s order for a

move into east Tennessee. His own force had been much reduced. Thousands had

been diverted to Grant’s operations in Mississippi and Rosecrans’ in middle

Tennessee. Of those who returned from the former state, most had contracted malaria

and other river country afflictions and could not be of much help.[5]

As he waited for the return of some of his men, Burnside sent a raiding force

under Colonel William Sanders to soften the enemy forces. Sanders struck

Confederate garrisons and tore up railroads. Like Burnside, Confederate general

Simon B. Buckner, in command of the region, was low on men and could do little

to slow Sanders down. Sanders marched his cavalry to the gates of Knoxville,

the main city of East Tennessee. Pro-Confederate civilians volunteered to

strengthen the city’s defenses and man the big guns. Sanders found it unwise to

proceed further and graciously praised the civilians for their stubborn

courage.[6]

Sanders

returned to Burnside, as did portions of the IX and XXXII Corps from operations

against Vicksburg. Under pressure from the government, Burnside moved his army

south in August. To alleviate the stress of traveling on the rough mountainous

roads, Burnside split his force into five columns. They would converge into

three once past the Cumberland River and then unify past the Tennessee River in

Morgan County. The start of the campaign was rough going. The mountainous roads

would be hard on the wheels of the wagon train. They were also lengthy.

Burnside would be far away from his base of logistics. Normally this meant an

extensive wagon train, but the only viable route for wagons was through the

Cumberland Gap. Not wanting to assail this protected position head-on, Burnside

used thousands of pack mules to haul artillery and supplies through smaller

alternate gaps.[7] Burnside’s

cavalry screened his movements against Buckner’s force, which was about equal

in size to Burnside’s. Buckner enjoyed good rail communications, but could not

hope to hold the nearly fifty mountain passes in the north. He also expected

Burnside to reinforce Rosecrans in middle Tennessee, not appear suddenly

outside Knoxville, so he had sent most of his men there instead.[8]

Burnside forced the surrender of the town on September 9 and his forces fanned

out to defeat and drive out other Rebel outposts. Knoxville was filled with

Unionist refugees, and most Secessionist men had departed to serve in the

Confederate army. As a result Burnside and his army were enthusiastically

greeted as liberators. Burnside had captured or driven out almost all Rebel

forces, and having accomplished the long-desired goal of freeing Unionist East

Tennessee, attempted to resign while he had regained some of his lost glory.

Lincoln denied his request.[9]

Burnside

had some reason to be fearful of displeasing his superiors again. The War

Department sent him two orders which, with the number of men he had available,

were impossible to reconcile. He was told to send a sizeable portion of his

force to reinforce Rosecrans and also to hold East Tennessee and protect

Unionist civilians. He could not adequately protect East Tennessee if he sent

reinforcements to Rosecrans, so he decided to only obey the second order.[10]

Burnside had considerable resources, but they were stretched thin. He was

separated from other Federal forces. His only line of communication was a 160

mile route north to Kentucky. In his fairly exposed position he presented a

potential military target. When Grant learned of Longstreet’s move towards East

Tennessee, he could do little for Burnside. He had his hands full breaking the

siege at Chattanooga. Burnside would have to go it alone against one of the

Confederacy’s best Corps.

Burnside had the following force to contest Longstreet at the river and back north in Knoxville. As can be seen the full corps were not available, with the First Division of XXIII Corps noticeably absent.

IX

Corps: Robert B. Potter

First Division: Brigadier-General Edward

Ferrero

David

Morrison’s 1st Brigade

Benjamin C.

Christ’s 2nd Brigade

William

Humphrey’s 3rd Brigade

Second Division: Colonel John F.

Hartranft

Joshua

K. Sigfried’s 1st Brigade

Edwin

Schall’s 2nd Brigade

XXIII

Corps: Brigadier-General Mahlon D. Manson

Second Division: Brigadier-General

Julius White

Samuel R. Mott’s 1st

Brigade

Marshall W. Chapin’s 2nd

Brigade

Third Division: Brigadier-General

Milo S. Hascall

James W. Reilly’s 1st

Brigade

Daniel Cameron’s 2nd

Brigade

William A. Haskins’

Provisional Brigade

Cavalry

Corps: Brigadier-General James M. Shackelford

First Division: Brigadier-General

William P. Sanders

Frank Wolford’s

1st Brigade

Emory S. Bond’s 2nd

Brigade

Charles D. Pennebaker’s

3rd Brigade

Second Division: Colonel John W.

Foster

Israel Garrard’s

1st Brigade

Felix Graham’s 2nd

Brigade

Derailed

Campaign

On

November 1 the Confederate First Corps withdrew from the siege around

Chattanooga. Its first destination was Sweetwater with its railroad station. Longstreet’s

campaign did not get off to a good start. There were two factors would plague

his efforts for the next couple months. First was the growing dissent within

the ranks of the First Corps’ generals. Longstreet started off with two

infantry divisions and Edward Porter Alexander’s artillery. He was also given

another battery under Leyden and Wheeler’s cavalry corps. This gave him about

15,000 men. The first infantry division was under Lafayette McLaws, a

long-running friend and subordinate of Longstreet’s. Leadership of the second division was a source

of division. It had been John Bell Hood’s, but Hood was out with an injury.

Rules of seniority held that Evander Law would take up command. In fact he had

assumed control of the division at Chickamauga after Hood was wounded. However

Micah Jenkins, another brigade commander in the division, had caught the praise

and favor of Longstreet.

Longstreet

sought President Davis’ view on the matter. Davis suggested Law should take

command since he was senior, but made no firm directions. Longstreet decided to

promote Jenkins to divisional command. This move caused strife between Jenkins

and Law that would plague the division’s coordination throughout the campaign.[11]

Another issue concerned General Jerome Robertson, commander of the famed Texas

Brigade. Robertson had performed miserably at Chattanooga, failing to seriously

contest a Federal crossing that took pressure off the besieged city.

Longstreet, with Bragg’s assent, had him removed and arrested. But with a new

campaign immediately opening up, Bragg decided to reinstall Robertson for the

time being. Longstreet now had another bitter subordinate to contend with.[12]

Longstreet was responsible for creating and aggravating tensions within his

Corps. He was starting to emulate Bragg rather than Lee in how he managed his

subordinates.

|

| Micah Jenkins |

|

| Evander Law |

Following is the Confederate order of battle at the start of the campaign. Another brigade under Robert Ransom was ordered to join Longstreet from Western Virginia, but he would not link up with him until after the main battle.

First

Division: Major-General Lafayette McLaws

Joseph B. Kershaw’s South Carolina

Brigade

William T. Wofford’s Georgia Brigade

Benjamin Humphreys’ Mississippi Brigade

Goode Bryan’s Georgia Brigade

Second

Division: Brigadier-General Micah Jenkins

Micah Jenkins’ South Carolina

Brigade commanded by Colonel John Bratton

Evander Law’s Alabama Brigade

Jerome B. Robertson’s Texas Brigade

George Anderson’s Georgia Brigade

Henry Benning’s Georgia Brigade

Artillery:

Colonel Edward P. Alexander

Cavalry

Corps: Major-General Joseph Wheeler

First Division: John T. Morgan

Second Division: Frank Armstrong

The

second issue plaguing the campaign was the inefficiency of the Confederate

military and government in Tennessee. Longstreet had envisioned a lightning-fast

campaign utilizing the East Tennessee & Georgia Railroad. He would strike

and destroy Burnside’s army while it was divided. Indeed, Burnside’s men were

scattered all over the region. One brigade had to protect and keep the

Cumberland Gap open. The Cumberland Gap was the long, but only decent route for

reinforcement and supply between East Tennessee and Kentucky. Some men had to

garrison Knoxville, the most important town, and others were scattered about

protecting other important points. If Burnside could consolidate the bulk of

these units, he would have parity or even superiority in numbers. Longstreet

had to strike hard and fast.

Unfortunately

the railroad system was a mess. There were not enough cars available and the

engines carrying them were of degraded quality. Thus some of the men and

equipment got to go by rail while the rest had to get to Sweetwater on foot.

Edward Porter Alexander’s artillery was given priority and the guns were

mounted on trains but, “owing to the inefficiency of the railroad

transportation” the artillery did not all reach Sweet Water Station until

November 13. To quicken the pace as much as possible, the artillerists were

“required to pump water for the engine and to cut up fence rails for fuel.”

Longstreet was also blocked by the Tennessee River, and had to wait days for

the pontoon bridges to arrive. Once finally constructed, the pontoon bridge was

so weak against the Loudon’s currents that it broke away. When finally

reconstructed, it was said to look like an “S.” A Federal cavalryman who

observed this wrote later that if not for their engineering woes, the

Confederates would have crossed quicker and caught the Federals by surprise. The

bridge did hold well enough for the army to get over. Bragg contributed to

First Corps’ delays. He promised to send wagons and supplies to expedite the

campaign, but failed to do so. This broken promise “beset the entire campaign.”[13]

The Fighting

Retreat

Despite

the issues befalling Longstreet’s force, the Federals were still in danger of

being cut off and destroyed before they reached Knoxville. As his men crossed

the Tennessee, Longstreet learned that the Federal IX Corps was only a few

miles off to the east. If he moved quickly, he could cut it off at Lenoir

Station and then destroy it. Burnside initially also was eager to give battle,

planning to contest the Confederates after they crossed. However he quickly

changed his mind. Grant suggested that he try to draw away Longstreet and make

his job at Chattanooga easier. Also, while Burnside technically had more men

than Longstreet, they were scattered around East Tennessee. He would actually

be outnumbered if he faced Longstreet at the Tennessee River. His new strategy

incorporated Grant’s strong advice. It was to draw the Confederates after him,

taking them further away from Chattanooga to soften Bragg’s Army there. While

the First Corps slogged their way to Sweetwater, Burnside took advantage of

their delays. He would get as much of the IX and XXXII Corps as he could to

Knoxville. Knoxville had earthworks, a supply depot, and a favorable Unionist

population surrounding it. Burnside believed he could hold for a while there

until the situation at Chattanooga was resolved. Then Grant could send aid.[14]

Longstreet’s

army was across the river by the night of the 13th, challenged only

by a brief foray from General White’s brigade. The skirmishing is reported to

have inflicted no casualties on the Confederates and did little to slow them

down.[15]

Now Burnside’s army was in a desperate retreat. Rain dropped from the sky,

turning the already poor roads into mud. One veteran of the retreat recalled

that a “liberal mixture of water with the red clay soil had produced a substance

not so slippery as soap, nor so sticky as wax, yet… qualified to receive the

appellation of Tennessee mud…” In order to make time, Burnside’s men had to

abandon many of their wagons. Their mules were needed to pull the artillery

pieces and their caissons through the deep mud. The mud deprived men of their

boots, forcing them to spend time rescuing their footwear. Heavy horses and

mules often sank and teams of men had to drag them out.[16]

Men

were left in the rear to destroy abandoned wagons and their supplies, but could

not do it fast enough. Confederate soldiers, always suffering from shortages in

almost everything, enthusiastically came upon these gifts laden with food,

blankets, and other essentials. The sacrifice of supplies worked out well for

the Federals, who beat the Rebels to Lenoir Station. There they gathered straw

to make beds, eager to finally get some sleep. Their hopes were dashed when in

just an hour they were put on the march again. Burnside was not ready to

contest Longstreet yet. Furthermore, Longstreet was already attempting to cut

off his army again, this time by beating the Federals to Campbell Station. Once

again the Federals trudged through the mud, losing wagons and worn-out mules.

Artillerists in one Rhode Island battery could not haul all of their ammunition

and had to destroy two caissons. Exhausted stragglers sat down by the road,

only motivated to move when Rebel skirmishers appeared. During their pursuit

the Rebels came “upon a park of eighty wagons, well loaded with food, camp

equipage, and ammunition, with the ground well strewn with spades, picks, and

axes.” This time Confederate cavalry intercepted Hartranft’s division. However,

this light force was incapable of stopping a full division and had to stand

aside while the Federals marched past to Campbell Station. Longstreet had sent

the bulk of Wheeler’s cavalry ahead, on the other side of the Holston River, to

strike Knoxville from the South. While this helped besiege the city later on,

Wheeler’s thousands-strong force could have been better used to dash ahead and

get in front of the Federals, trapping them between two Rebel forces (this

judgment, of course, involves a little hindsight. Longstreet did not learn how

close the separated IX Corps until after he dispatched the cavalry).[17]

Around

noon on the 16th, The Federals once again won the race, but this

time only by a quarter of an hour. A cavalryman scouting out the army’s rear

spotted the 8th Georgia regiment and, after gunning down one

soldier, rushed back to warn the rest of the army. General Edward Ferrero, a

dance school instructor and commander of one of the Federal divisions, rose

from his meal and announced “Gentlemen, the ball has opened.” The IX Corps

quickly deployed to meet the oncoming Confederates. Longstreet’s plan for the

battle was to have McLaws’ division confront the IX Corps and hold it in place.

Jenkins’ division on the right would attack the Federal left. Law would command

two of Jenkins’ brigades and flank the enemy, rolling them up and cutting off

the road to Knoxville.[18]

The

Union’s hasty defense soon gave way. The Federals made the “nearly fatal

mistake” of trying to regroup in a ravine, exposed to fire from the higher

ground above them. One officer of the 17th Michigan, Major F.W.

Swift, seized the colors and barked at his men to run no further. General

William Humphreys also stepped in to stop the rout. Finally rallying, the men

were able to beat off the initial attack and return to a retreat, this time in

more orderly fashion.[19]

The confrontations between the infantry were brief and usually amounted to mere

skirmishes. Several generals described the Battle of Campbell’s Station as an

artillery battle. Confederate artillery fire sent the Federals withdrawing,

though the actual effectiveness of their shells proved lacking. Too many of

them exploded prematurely, leaving the Union ranks almost unscathed. One of the

faulty shells went off in the barrel of a gun, destroying it. Federal

counter-fire was more effective. In addition to dueling with the Confederate

guns, they slowed down the Rebel pursuit. If the enemy infantry got too close

they switched over to canister fire.[20]

|

| This depiction of Battle of Campbell's Station currently hangs at the Campbell Station Inn |

The

real problem for Longstreet’s men was coordination. McLaws’ division engaged

the enemy as planned, but the Federals withdrew rather than hold their ground.

This meant that quicker action was required from Jenkins. However, his brigades

moved out of step with each other. Law’s two brigades had moved too far to the

left. They not only bumped into Anderson’s brigade on their left, but came in

front instead of behind the Federals. Attempts to rectify the situation failed

and the IX Corps always stayed a step ahead of Jenkins’ division. Jenkins was

so furious with Law’s failure that he ascribed petty ulterior motives to it. He

believed that Law, out of jealously over the divisional command, had

purposefully mismanaged his movements to make him look bad. The biased Longstreet was inclined to agree

with his favorite, worsening the strife at the command level. Moxley Sorrel,

Longstreet’s Chief of Staff, lamented years later on the state of the second

division’s leadership, “Ah! Would that we could have had Hood again at the head

of his division.”[21]

Sensing that all was not right with their leadership, the rank-and-file began

to lose their enthusiasm. They even grew critical of Longstreet after his two

failures to envelop the enemy. Instead of using the affectionate “Old Pete,”

they gave him the nickname “Peter the Slow.”[22]

Longstreet’s

only hope now for a quick and successful campaign was to hit the Federals before they could

solidify their positions at Knoxville.

Sources

Memoirs

Alexander,

Edward Porter. Military Memoirs of a

Confederate: A Critical Narrative. New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1907.

Brearley, Will

H. Recollections of the East Tennessee

Campaign. Detroit: Tribune Book and Job Office, 1871.

Cutcheon,

Byron M. Recollections of Burnside’s East

Tennessee Campaign of 1863. 1902.

Longstreet,

James. From Manassas to Appomattox:

Memoirs of the Civil War in America. J.B. Lippincott and Co., 1896.

Sherman,

William Tecumseh. Memoirs. Penguin

Books edition, 2000.

Sorrel, G.

Moxley. Recollections of a Confederate

Staff Officer. New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1917.

Wilshire, Joseph W. A Reminiscence of Burnside’s Knoxville Campaign: paper read before the Ohio Commandery of the Loyal Legion, April 3rd, 1912. Cincinnati: 1912.

Other Primary Sources

The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Vol. XXXI: Operations in Kentucky, Southwest

Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Alabama, and North Georgia. October

20-December 31, 1863. Washington D.C.

1894.

Poe, Orlando M.

“The Defense of Knoxville” in Battles and

Leaders of the Civil War Vol. III. New York: The Century Co., 1888

Secondary Sources

Cozzens, Peter The Shipwreck of their Hopes: The Battles

for Chattanooga. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Glatthaar,

Joseph T. General Lee’s Army: From

Victory to Collapse. New York Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Hess, Earl J. The Civil War in the West: Victory and

Defeat from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. University of North

Carolina Press, 2012.

Korn, Jerry. The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to

Missionary Ridge. Time-Life Books, 1985.

Markel,

Joan L. Knoxville in the Civil War.

Arcadia Publishing Inc., 2013. Hoopla Edition.

-

“Knoxville: a Near-Death Experience,” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/knoxville-near-death-experience, accessed December 3, 2020

Marvel,

William. Burnside. University of

North Carolina Press, 1991.

McPherson,

James. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil

War Era. Oxford University Press, 1988.

Mendoza,

Alexander. Confederate Struggle for

Command: General James Longstreet and the First Corps in the West. Texas

A&M University Press, 2008.

Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet: The Confederacy’s

Most Controversial Soldier – A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster,

1993.

Wilkinson,

Warren and Steven E Woodworth. A Scythe

of Fire: A Civil War Story of the Eighth Georgia Infantry Regiment. New

York: HarperCollins, 2002.

[1] Alexander Mendoza, Confederate Struggle for Command: General

James Longstreet and the First Corps in the West (Texas A&M University

Press, 2008), 24-26; Peter Cozzens, The

Shipwreck of their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga, (University of

Illinois Press, 1996), 28-29.

[2] Longstreet, James, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the

Civil War in America, (J.B. Lippincott and Co., 1896), 465; Chapter III of

Cozzens’ Shipwreck of their Hopes

gives a summary of the plot against Bragg and Davis’ visit.

[3] Mendoza, 107-109; Jeffrey Wert, General James Longstreet: The Confederacy’s

Most Controversial Soldier – A Biography, (New York: Simon & Schuster,

1993), 338-339; Jerry Korn, The Fight for

Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge, (Time-Life Books, 1985), 100.

[4] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era,

(Oxford University Press, 1988), 304-305.

[5] William Marvel, Burnside, (University of North Carolina

Press, 1991), 264-267.

[6] Joan L. Markel, Knoxville in the Civil War, (Arcadia

Publishing Inc., 2013, Hoopla Edition), 87.

[7] Marvel, 270; Earl J. Hess, The Civil War in the West: Victory and

Defeat from the Appalachians to the Mississippi, (University of North

Carolina Press, 2012) 187; Korn 101.

[8] Marvel, 271-273; Hess, 188.

[9] Marvel, 276-280; Markel, 89.

[10] Marvel, 285-289.

[11] Longstreet, 467-468; Wert,

336-338.

[12] Mendoza, 110-112.

[13] OR XXXI, 478; E. Porter Alexander, Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A

Critical Narrative, (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1907), 481; G. Moxley Sorrel,

Recollections of a Confederate Staff

Officer, (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1917), 205-206; Joseph W.

Wilshire, A Reminiscence of Burnside’s

Knoxville Campaign paper read before the Ohio Commander of the Loyal Legion,

April 3rd, 1912, (Cincinnati: 1912), 19-21.

[14] Marvel, 300-307.

[15] OR XXXI, 377-378, 383, 386.

[16] OR XXXI, 345; Will H. Brearley, Recollections of the East Tennessee Campaign,

(Detroit: Tribune Book and Job Office, 1871), 14-15.

[17] OR XXXI, 346-347; Brearley, 18;

Longstreet, 491; Mendoza, 119; Korn, 108-109; Joan L. Markel, “Knoxville: a

Near-Death Experience,” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/knoxville-near-death-experience, accessed December 3, 2020.

[18] Warren Wilkinson and Steven E

Woodworth, A Scythe of Fire: A Civil War

Story of the Eighth Georgia Infantry Regiment, (New York: HarperCollins,

2002), 274; Byron M. Cutcheon, Recollections

of Burnside’s East Tennessee Campaign of 1863. 1902, 12-13; Mendoza, 120.

[19] Brearley, 20-21.

[20] OR XXXI, 478.

[21] OR XXXI, 526-527; Sorrel, 207;

Mendoza, 125.

[22]Mendoza, 125.

No comments:

Post a Comment