1.

First, this

battle came about as Stuart, separated from the main body of Robert E. Lee’s

Army of Northern Virginia, tried to reconnect his three cavalry brigades. The

Federals at Hanover stood in his way of getting to Gettysburg, where he thought

he might find Lee. If he had plowed through Kilpatrick’s rear guard or been

fortunate enough to arrive there after the Federals were gone, he would have

gotten to Gettysburg at least on July 1, seriously altering the course of

events.

2. Secondly, it was the first battle where George Armstrong Custer, one of the most famous

cavalrymen in US history, held field command. He had so far spent most of the

war as a capable staff officer. This was his first serious test.

Stuart’s Third

Ride

|

| Jeb Stuart |

General Jeb Stuart was one of the top heroes of the Confederacy. Twice in 1862 he had ridden a complete circuit around the Union Army of the Potomac, creating chaos in its rear and swallowing up wagons of supplies for the constantly undersupplied Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. In the Battle of Chancellorsville, in May of 1863, he had taken over the wounded Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Corps and led it to victory. However, the dashing cavalier’s pride was wounded when the Federal Cavalry caught him off guard at Brandy Station. Though victorious in the war’s largest cavalry fight, he was not used to being on the end of a surprise. He had previously dished out such surprises himself. Now he was tasked with screening the Army of Northern Virginia as it embarked on its second invasion of the North. He had so far engaged the Federals in several pitched battles at Aldie (June 17), Middleburg (June 18-19), and Upperville (June 21). These were mostly tactical draws, but the Federal cavalry, once a hapless and disorganized antagonist, had definitely improved and was giving him a hard time.[1]

On

the rainy night of June 23, Henry B. McClellan, Jeb Stuart’s Chief of Staff,

received a message passed through Lieutenant General James Longstreet by the army’s

commander Robert E. Lee. Awakening the general, McClellan handed him the order.

Lee wanted Stuart to operate beyond the right flank of the advancing

Confederate army. Lee favored open-ended orders which deferred to his

subordinates’ judgment. This was no exception. The letter gave Stuart

permission to commit a raid for supplies if General Joseph Hooker, commander of

the Army of the Potomac, continued to move his army slowly. If Stuart did this, it was

expected that he could have communication with Jubal Early’s division from

Richard Ewell’s I Corps. If such a venture appeared too risky, Stuart was to

head back and reunite with the main Confederate body. His pride still wounded

by the surprise attack at Brandy Station, and also chopping at the bit to

perform another grand feat, Stuart of course planned for another grand raid.[2]

Stuart

had three brigades for the task. General Wade Hampton, the prominent scion of a

very wealthy planter family in South Carolina, commanded several regiments of

North and South Carolinians as well as an assortment of unattached legions.

General Fitzhugh Lee, the nephew of Virignia’s favored son Robert E. Lee,

naturally led a brigade of fellow Virginians. Speaking of Lee, Marse Robert’s

second son William H.F. Lee was also the commander of a cavalry brigade.

However he was out with a wound from Brandy Station so Colonel John R.

Chambliss, Jr. stepped up to command in his place. His men included the 2nd

North Carolina Cavalry and more Virginia regiments. Here is the order of battle

for Stuart’s cavalry.

Major-General

Jeb Stuart

Brigadier-General Wade Hampton

1st North

Carolina: Colonel John Black

1st South

Carolina: Major T.J. Lipscomb

2nd South

Carolina: Colonel Pierce Young

Cobb’s Georgia Legion:

Colonel Joseph F. Waring

Jeff Davis’s Mississippi

Legion: Lieutenant-Colonel Jefferson C. Phillips

Phillips’ Georgia Legion

Brigadier-General Fitzhugh Lee

1st Maryland

Battalion: Major Harry Gilmor

1st Virginia:

Major William A. Morgan

2nd Virginia:

Colonel Thomas T. Munford

3rd Virginia:

Colonel Thomas H. Owen

4th Virginia:

Colonel Williams C. Wickham

5th Virginia:

Colonel Thomas L. Rosser

Colonel John R. Chambliss

2nd North

Carolina: Lieutenant-Colonel William H.F. Payne

9th Virginia:

Colonel Richard L.T. Beale

10th

Virginia: Colonel James L. Davis

13th

Virginia: Captain Benjamin F. Winfield

On

June 24 Stuart moved his three brigades north toward the town of Haymarket.

Immediately his operation went awry. He ran into Major-General Winfield Scott

Hancock’s II Corps of the Federal Army. Hancock’s artillerists fired at the

horsemen and the Confederate cavalry had no intention of proceeding along their

planned path. Per Robert E. Lee’s instructions, Stuart could now either

backtrack and abandon his ride into the Federal rear or take an even wider

detour. Unwilling to abandon another chance at glory, and perhaps still wanting

to erase the sting of Brandy Station, he chose the latter option. He sent a

messenger to Lee to inform him of Hancock’s position. With knowledge of a Union

corps’ position, the cavalry that remained with the main army would have been

able to track the enemy’s movements and ensure that the infantry did not

stumble blindly into an unwanted battle. For some reason the messenger failed

to reach his destination. Now Stuart, taking a wider arc, was too far from

Lee’s army to communicate with it. Worse, tens of thousands of Federals marched

between them.[3]

Stuart’s

ride at first looked promising. His horsemen made several successful raids, the

crowning achievement the capture of over 100 wagons at Rockville, Maryland. However,

days passed without any communication with Lee. Tired, deep behind enemy lines,

and encumbered by the wagon train, they began to feel isolated and in danger.

One pitched battle with either the Federal cavalry, recently proven to have

become a formidable antagonist, or one of the infantry corps could result in

Stuart’s doom. On June 30, Stuart’s cavalry crossed into Pennsylvania, still

not knowing where Lee’s army was.[4]

Stuart

planned to reunite with his superior soon.

Despite his desperation, his men marched at an unhurried pace. There

were three reasons for this. One was that many of the men and horses could use

a reduced pace of campaigning after weeks of raiding and skirmishes. Second was

that Stuart clung to the supply wagons taken at Rockville a couple days before.

He was loathe to separate from such bountiful prizes. Writing after the war,

William Blackford, Stuart’s engineer, claimed that the vehicles “began to interfere

with our movements, and if General Stuart could only have known what we do now

it would have been burned.” Thirdly, the Federals had yet to mount a determined

pursuit, with only 300 troopers form the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry

anywhere near him.

They

reached a literal fork in the road. In a great what if of history, Stuart chose

to take the road to Hanover rather than Gettysburg. If he had taken the latter

option, he would have linked up with Heth at Gettysburg with only General John

Buford’s Federal cavalry to oppose him. This would have drastically changed the

face of the Battle of Gettysburg, perhaps giving Lee a more advantageous

command of the heights surrounding the cross roads town. This of course is

obvious in hindsight. The road through Hanover also led to Gettysburg on a

shorter route and there was no reason why Stuart, unaware of what lay ahead,

would have not taken it. Chambliss sent parts of his command forward to look

for fresher horses to use and to see if any Federals were about. The men had

many reasons to avoid a fight at this point, mainly that they were exhausted.

Days later one soldier grumbled in a letter home, “Both men and horses being

worn out, all of us regarded the prospect of a fight with no little regret and

anxiety.”[5]

Kill-Cavalry’s

Division

The man who Stuart would square off with at Hanover was General Judson Kilpatrick. Kilpatrick commanded the Third Division of the recently reorganized and improved Federal Cavalry Corps. He was among the war’s more controversial officers. He was brave and daring, but also loose with his men’s lives. His reckless management of his forces throughout the war and resulting high casualties gave him the nickname “Kill-Cavalry.” Around the time Stuart crossed into Pennsylvania, he was working to gather together his division of two brigades under Elon J. Farnsworth and George Armstrong Custer.[6]

Farnsworth,

27 years old in just one month, had fought in his uncle’s 8th

Illinois Cavalry regiment and then became a staff officer. One staff he landed

on belonged to General Alfred Pleasonton, commander of the Army of the

Potomac’s cavalry. He evidently impressed Pleasonton because on June 29 he was

suddenly promoted from captain up to brigadier-general (quite the leap in rank).[7]

Farnsworth’s brigade was more experienced than Custer’s. Three of his regiments

had signed up back in 1861. The exception was the 18th Pennsylvania.

It had formed the previous summer, but had so far only in engaged in light

confrontations.[8]

One

regimental commander under Farnsworth who would play a large role at the Battle

of Hanover was Major John Hammond of the 5th New York. John Hammond

was a scion of the prominent Hammond family in Crown Point, New York (they ran

the iron works there). He raised his own company of cavalry and joined the 5th

New York, eventually rising to overall command of the regiment. He was very

popular and respected amongst his men, with the regimental history praising him

for his “thorough” but not “severe” discipline, quick-thinking tactical skills

and “indomitable will.”[9]

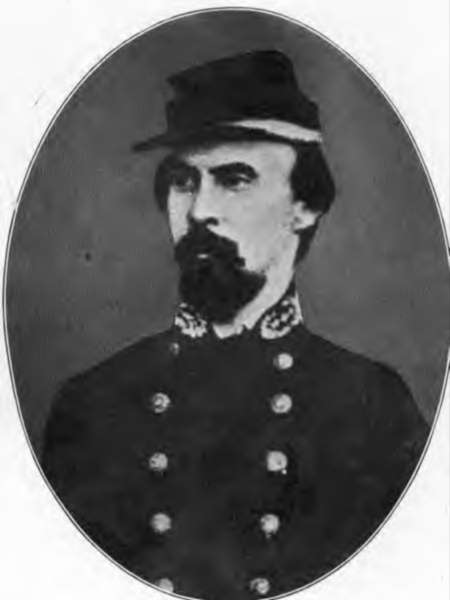

The

commander of the Michigan Brigade is much more well known to history. The

ambitious and still quite young George Armstrong Custer had long desired a

field command. It had taken him over two years of war for him to get his

chance. He had served with distinction on the personal staffs of both Generals

George B. McClellan and Phil B. Kearney, yet his outspoken Democrat views had

put him at odds with Michigan’s Republican Governor Austin Blair. Blair

frequently blocked his requests for a proper command. The young warrior finally

got his break when he participated at the recent Battles of Brandy Station and Aldie.

General Pleasanton was so impressed that he gave him control of the Michigan

Brigade. This included the 1st, 5th, 6th, and

7th Michigan Cavalry regiments. This brigade had only just been put

together and was quite the mix. The 1st Michigan had battle-hardened

veterans who participated heavily in the Second Bull Run campaign. The 5th

Michigan had been stuck on garrison duty around Washington D.C. (it was led by

future Republican governor, senator, and secretary of war Russell Alger). The 6th

and 7th Michigan had just been mustered into service.[10]

Custer

assumed command in the midst of the Gettysburg campaign, just days before the

battle that lent the operation its name. The 5th and 6th

Michigan was detached at Littlestown, so Custer for the moment only oversaw the

1st and 7th. He immediately made an impression due to his

appearance. He wore a hussar-style jacket with plenty of gold lace, a dark blue

sailor’s shirt, silver stars on his collar, a scarlet cloth wrapped around his

neck, and a slouch hat. Completing the get-up was his long blonde hair, which

ended in ringlets, and large drooping mustache. Edward Longacre, who

specializes in studying the cavalrymen of the Virginia theatre of war,

theorizes that his outlandish attire and incredible amount of hair was meant to

conceal his youthful age. After all, most if not all of his subordinate

officers were older than him, some by a good many years.[11]

This

is the Union order of battle:

Cavalry

Corps, Third Division: Brigadier-General Judson Kilpatrick

First Brigade: Brigadier-General

Elon J. Farnsworth (left photo)

5th New York

Cavalry: Major John Hammond

18th

Pennsylvania Cavalry: Lieutenant-Colonel William P. Brinton

1st Vermont

Cavalry: Colonel Addison W. Preston

1st West

Virginia Cavalry: Colonel Nathaniel P. Richmond

Second Brigade: Brigadier-General

George A. Custer (right photo)

1st Michigan

Cavalry: Colonel Charles H. Town

5th Michigan

Cavalry: Colonel Russell A. Alger

6th Michigan

Cavalry: Colonel George Gray

7th Michigan

Cavalry: Colonel William D. Mann

Attached Horse Artillery

2nd United

State, Battery M: Lieutenant Alexander C.M. Pennington, Jr.

4th United

States, Battery E: Lieutenant Samuel S. Elder

Kilpatrick

had to get all these regiments together as the Union Army, now under the

command of Major-General George Gordon Meade, was heading in the direction of

Gettysburg. Custer, still in Maryland, was ordered to advance into Pennsylvania

via the Emmitsburg Road and link up with Farnsworth’s brigade. Custer’s brigade

itself would have to link up. He personally headed the 1st and 7th

Michigan and Lieutenant Pennington’s Battery M. Colonel Russell Alger would

guide his own 5th Michigan as well as the 6th under

Colonel George Gray. They were currently around Littlestown to the west of

Hanover. The Third Division’s entry into Pennsylvania provided a boost in

morale. They were not accustomed to campaigning in friendly territory, where

the citizens greeted them with smiles, cheers, and food and drink.[12]

Such

a welcome reception awaited them at Hanover. The citizens in Hanover were

enthusiastic at the arrival of the first of Kilpatrick’s horsemen, consisting

of the 1st and 7th Michigan. Confederate cavalry had

recently entered other towns in the region. They seized food and animals, along

with other useful property, and compensated civilians with the never valuable

paper currency of the Confederacy. The people of Hanover had not suffered such

pillaging, but they were nevertheless relieved to be visited by their own

soldiers rather than Stuart’s raiders. The grateful Hanoverians showered the

riders with flowers, buttermilk, and cigars.[13]

By

10 AM Kilpatrick’s division, save for the 18th Pennsylvania and the

detached 5th and 6th Michigan, had entered or passed

through the town. The 5th New York took a break on Main Street to

rest while the wagon train under the rear guard of the 18th

Pennsylvania came up. Some in this regiment fanned out south of Hanover to look

out for Confederate cavalry, but did not expect to find any. Though

Kilpatrick’s division had been tasked with intercepting Stuart, they did not

expect to run into him on this day. One of the Pennsylvanians wrote decades

later, “…It was not thought we were in such close proximity to him as we in

fact were on this 30th of June.” As it turned out, both forces were

in for a surprise, much like the two greater armies at the approaching Battle

of Gettysburg. [14]

An Encounter

Battle

One interesting thing about the Battle of Hanover is that, like the imminent Battle of Gettysburg, it was an encounter battle. An encounter battle is when two forces unexpectedly run into each other and have no choice but to fight an unplanned engagement. Actually, such engagements in the Civil War were fairly common among skirmishes and smaller battles, where detached infantry units and/or cavalry forces were likely to bump into each other. Gettysburg was a rare example of two entire armies stumbling into each other.

Stuart’s

brigades on June 30 were arranged thus. Fitzhugh Lee was to the west near

Littlestown. Chambliss headed the advance, while Hampton’s men guarded the

wagon train. Lee learned that Kilpatrick’s

cavalry was in Hanover. He sent a courier with a message to warn Stuart that he

was marching right into a Federal division. Enemy horsemen discovered the

courier en route and captured him. As a result Stuart continued straight into an

unwanted battle.[15] The

first fighting of the day occurred between a Pennsylvanian battalion (less than

a dozen men) under Captain Thaddeus Freeland and a larger force from the 13th

Virginia Cavalry. The two groups surprised each by a blacksmith shop on a hill.

After a moment of awkward silence, Freeland’s men whipped out their breech-loading

rifles, fired a few volleys, and fled, scoring one kill.[16]

One

40-man contingent from the 18th Pennsylvania, under Lieutenant Henry

C. Potter, responded to a civilian complaint that “The rebs have taken my

horses and cows!” They saw horsemen to their east. Some wore blue coats so

Potter assumed that it was Freeland and his detachment. Potter rode closer with

plans to reprimand the captain for misbehavior. Then he saw that there were

about 60 of them, too many to be Freeland’s group. These Confederate riders

(probably from the 13th Virginia) were the advance guard of

Chambliss’ brigade. The opposing columns took parallel roads that would link up

ahead. The Confederates got there first and stopped while Potter’s men

resolutely kept up their marching pace. As he got closer, the leading

Confederate officer called on him to surrender. Potter responded by signaling a

charge. The men drew their revolvers and unleashed lead. This move came so

quickly that they surprised and scattered the Confederates, enabling them to

pass through towards Hanover. The Confederates quickly collected themselves and

gave chase. Potter led them into the

rear guard. Facing dismounted Pennsylvanians protected by fences, the pursuers

broke off and waited for the rest of the southern cavalry to arrive.[17]

Chambliss

brought up the rest of his brigade, planning to break through the

Pennsylvanians into Hanover. Colonel Richard Beale of the 9th

Virginia Cavalry deduced that “the enemy’s troops must have been raw levies, as

the side of the pike was strewn with splendid pistols dropped by them as they

ran.” Beale personally partook in the spoils, selecting two of the firearms for

himself. Based on this initial encounter, the Confederates assumed that these

Federal rear guards were the only force around, and that the town was as good

as theirs.[18]

Stuart learned of the unfolding fight. With reports of one easily panicked

regiment in the way, Stuart sent one of his staff officers to press Chambliss

to “push on and occupy the town,” but not to chase the Federals too much. He

simply wanted to get his brigades through Hanover and to where he estimated the

Army of Northern Virginia to be. As it turned out, they were in for a rude

surprise.[19]

Chambliss’

Confederates advanced, the 2nd North Carolina taking the lead, and

opened up with their artillery while their horsemen charged. They were positioned

so that they would smash right into the center of the 18th Pennsylvania

column from the east. The Pennsylvanians tried to put up a fight against the North

Carolinians, but were overwhelmed. 25 men under Lieutenant T. P. Shields were

the only ones to put up a good fight. Since the rest of the regiment had given

way, however, Shields and his men were cut off. Many managed to escape, but

Shields and a few others ended up as prisoners. The Pennsylvanians fled for the

streets and yards of Hanover. In the town the 5th New York had heard

one of the Confederate cannons fire. It was the only one they heard and assumed,

amidst the festive mood of the Hanoverians, it was a “friendly salute for our

troops” by local militia cannon. One New York trooper recalled, “In about two

minutes came another boom, and this time a shell came screeching up the street,

and in a few minutes the pot and kettle brigade came dashing through our ranks,

yelling that the whole rebel army was right after them.” The retreating

troopers mixed with the wagon-clogged streets to create a confusing scenario.

The women and children, who had been giving out gifts and treats to the

soldiers, ran about in sudden terror. The 1st West Virginia and 1st

Vermont, hearing the commotion, turned about and headed to reinforce.[20]

It

took time for most of the troopers in town to collect their senses. This was

not true for New York Privates Augustus Forsyth and Henry Spaulding. They were

guarding a wagon full of medical supplies when the shooting broke out.

Spaulding seized the reins of the wagon and drove off while Forsyth fended off

Rebel horsemen with his revolver.[21]

Outside of the unfolding melee, Chambliss deployed his artillery on either side

of the Westminster Road, leading into town from the southwest. They commenced a

bombardment which added to the confusion and angered the civilians. The Hanover Citizen declared the shelling

“an act wholly unworthy of a civilized people and contrary to the usage of

civilized warfare.”[22]

|

| https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/hanover-first-phase-fighting-june-30-1863 |

Charges and

Counter-Charges

Elon

Farnsworth, who like Kilpatrick had already ridden far out of town, personally

arrived and rallied the men for a second push. He pulled out his saber, gave a

great shout, and led his reinvigorated brigade forward. This charge was more

successful than the first and the Confederates reeled. The 2nd North

Carolina fell into disorder as its commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel

William Payne, went down. A bullet took down Payne’s horse as it was running.

The unfortunate colonel flew off his mount, headfirst into an open vat of dye

in the tannery yard. The two opposing sides found themselves mixed up, with

violent results. Small groups of Federals and Confederates shot and wrestled

each other in the streets and yards. Civilians could actually see men kill and

maim each other right outside their windows. Private Thomas Burke of the 5th

New York saw a wounded fellow from his regiment locked in a fight with the

color bearer of the 13th Virginia. Burke sped his horse to the

scene, shot the flag bearer dead, and captured the flag himself, along with two

other Virginians. Adjutant Gall of Hammond’s staff also participated in the fight

and died when a bullet sliced into his left eye.[24]

Stuart

found the intensifying fight to be an unpleasant surprise. Desperate to get

back to Lee, he had hoped that Chambliss would break through the supposedly

light resistance at Hanover. Instead Chambliss’ men were running out of town.

Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade could not come at the moment as it was locked in a

confrontation with Colonel Gray’s 6th Michigan near Littlestown. The

5th Michigan under Colonel Alger was already well on its way to

Hanover and was not there to support its sister regiment. The Confederate

artillery spotted the Federal troopers in column and struck them with shell

shot, killing and wounding some horses and men. Lee’s brigade of course

outnumbered Gray’s one regiment, as much as 4 to 1, but the colonel put up a

good fight, so far ignorant of the odds. First his men pushed back Lee’s

skirmishers. Then they ran into the rest of the enemy and realized their

situation. Lee’s horse artillery was situated to bombard his right flank, and

his riders were all lined up and ready to charge. Gray realized he would lose

his entire command if he did not disengage. The sacrificial lion came in the

form of Major Peter A. Weber, placed in charge of companies B and F. Assisted

by local civilians bearing their personal firearms, Weber fought off three

attacks while the rest of the regiment escaped to link up with the 5th

Michigan. Weber lost many of his men, but kept much of Lee’s brigade from

getting to Hanover.[25]

Hampton

was also slow in coming to Chambliss’ aid, his horsemen stretched over 8 miles

to guard the captured wagon train. His soldiers could only ride up piecemeal

and they would not get there until midafternoon. Thanks to the Michiganders’

stubborn performance at Littlestown and the situation with the wagons, Stuart

grew nervous. The cavalier rushed to rescue the situation. The 2nd

North Carolina was in full retreat. Stuart, riding with William Blackford and a

few others, tried to rally them, but failed thanks to the “hot skirmish fire” emanating

from Hanover’s buildings. According to Blackford, some of the shooters were

Hanoverian citizens, eager at the chance to pitch in with their blue-clad boys

and defend their homes.[26]

Stuart’s

small party occupied a field by Westminster Road, on which Farnsworth’s brigade

advanced at him from the town. Stuart and his party pulled out their pistols

and fired at the Federal riders. Farnsworth’s men passed by, cutting off the

Confederate general’s ability to use the road as an escape route. He headed for

a stream with steep banks (15 feet high according to one veteran). Stuart, on his

bay mare Virginia, and Blackford, on Magic, rode by a hedge. Stuart, “with a

merry laugh,” told Blackford to rally the men and then vaulted with Virginia

over the hedge. It turned out that up to 30 Federal troopers were on the other

side. Stuart and Blackford hastened away with the enemy riders in hot pursuit.

The two Confederate officers steered their steeds towards the deep and quite

wide ditch and stream. At the last moment Stuart and Blackford’s horses leapt

and cleared the gully. Blackford remembered looking over at Stuart mid-leap and

seeing “this beautiful animal away up in mid-air over the chasm and Stuart’s

fine figure sitting erect and firm in the saddle.” The rest of the Confederates

with them either copied this feat or fell into the water. The pursuing troopers

dared not attempt to emulate the famed cavalier’s feat and screeched their

horses to a halt. So sudden was their stop that some men nearly flew off their

horses. Those Confederates unlucky enough to fall into the stream were able to

climb up the opposite side and escape. Stuart’s cavaliers characteristically

viewed this moment with amusement. “The ludicrousness of the situation,

notwithstanding the peril, was the source of much merriment at the expense of

these unfortunate ones.”[27]

William

Blackford had another close call. He was trying to calm down Magic when a

Federal sergeant came “bending low on his horse’s neck with his sabre ‘encarte’

ready to run me through.” Blackford thrust his left spur into Magic and got him

going, but not before the saber inflicted a wound between his left arm and

side. Once he had gotten to safety, Blackford turned and shook his fist at the

Federals in anger. Chambliss’ Virginians and North Carolinians regrouped and

were pleased to see Stuart still in command, and smiling as well. In the chaos

they heard that he had been surrounded and captured.[28]

Farnsworth,

seeing the entirety of Chambliss’ men in front of him, withdrew his men to

Hanover to erect barricades in the streets and alleys. As the opposing

cavalrymen separated, the affair turned into an artillery duel. Countermarching

Union batteries finally arrived and deployed north of town. The Confederate

artillery caused the greater share of terror, their shells also hitting the

streets and buildings of town. One shell broke through the balcony door of a home.

Thankfully for the family inside, the shell did not explode, but it did tear

through drawers, the second story floor, and the parlor room before embedding

in one of the house’s brick walls.[29]

Custer Gets to

Lead

|

| https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/hanover-second-phase-fighting-june-30-1863 |

The

sound of the battle had reached the ears of Custer’s Michiganders. Custer,

chopping at the bit to prove himself as a battlefield officer, had turned his

men about and arrived to find the town full of makeshift barricades, from which

Farnsworth’s men sparred with Chambliss’ brigade. Avoiding this mess, Custer

guided his two available regiments west. They lined up in view of Fitzhugh

Lee’s brigade and its artillery. To counter Lee and Chambliss’ artillery,

Custer placed Pennington’s battery alongside Elder’s on Bunker Hill, a height

north of town. The 1st Michigan served as the battery’s support with

the 1st Vermont from Farnsworth’s brigade supporting Elder. A battalion

from the 7th under Lieutenant-Colonel Litchfield advanced as

skirmishers. Three companies from the regiment moved into Hanover to help

Farnsworth man the makeshift barricades on the streets.[31]

To Custer’s joy the 5th and 6th Michigan arrived from

Littlestown. This was actually the first time they had seen each other.

Veteran James Kidd (a captain during the battle) recalled his introduction to

Custer:

|

| James H. Kidd |

It was here that the brigade first saw Custer. As the men of the Sixth, armed with their Spencer rifles, were deploying forward across the railroad into a wheatfield beyond, I heard a voice new to me, directly in rear of the portion of the line where I was, giving directions for the movement, in clear, resonant tones, and in a calm, confident manner, at once resolute and reassuring. Looking back to see whence it came, my eyes were instantly riveted upon a figure only a few feet distant, whose appearance amazed if it did not for the moment amuse me. It was he who was giving the orders. At first, I thought he might be a staff officer, conveying the commands of his chief. But it was at once apparent that he was giving orders, not delivering them, and that he was in command of the line.

Custer

sent Alger to a position at the edge of town. He ordered Gray to dismount his

600 men and form up on his left to challenge Chambliss. The 6th

advanced over the railroad tracks leading into town. Their target was a ridge.[32]

The

Michiganders wielded seven-shot Spencer rifles. These repeating rifles enabled

them to put up a heavy fire against Chambliss’ left flank and drove it back

towards the southern heights. They were now very close to Fitzhugh Lee’s horse

artillery. Gray adopted a stealthy approach. He had his men get down on their

hands and knees and crawl through high grass. Once they reached the foot of the

ridge, they rose up and delivered a surprise fire at the battery. Mounted

Confederates scurried away. About 15 ended up as prisoners. Thanks to the

Spencers the Federals still had plenty of shots left and they used them on the

artillerists themselves. The guns went silent. Lee saw the crisis unfolding and

hurried forward his men. They arrived before the 6th Michigan could

advance further and take the guns. The two sides exchanged shots, Gray refusing

to lose his foothold on the ridge and the Confederates keen to knock him and

his men off.[33]

To

the east Chambliss launched his own surprise attack. He went around the left

flank of the 6th Michigan and struck the 5th within the

town. Bolstered by a returning reconnaissance team from another regiment,

Colonel Russell Alger ordered a counterattack that drove Chambliss back,

“killing and capturing quite a number.” For the men in this regiment, who had

spent most of their service sitting around Washington, this was a pleasing

first battle, with only light casualties among their number. “Here we saw our

first dead rebs, and were highly elated over our first victory.”[34]

|

| Dave Gallon's portrayal of Custer at Hanover. Note the Spencer Rifles. |

Two Days’ Delay

Custer’s brigade made no further progress. Fighting died as the sun set. Hanover’s citizens had escaped Confederate occupation, but now, as they left their hiding places, they saw a more horrifying sight. Dead horses and men littered their yards. Sometimes they came across wounded men and helped carry them to the hospital. The Forney brothers, two boys who had been farming when the fighting broke out around them, found a severely wounded sergeant of the 2nd North Carolina on their front porch. This sergeant, Samuel Reddick, was slowly “struggling with death” due to a chest wound. They brought him inside and tended to him, but his life was slowly leaving him. He handed his Bible to the Forneys’ sister, begging her to send it home to his own sister. She had given him this Bible and he had promised to bring it over when the war ended. But “it has ended for me now.”[35]

Stuart

had no desire to fight any further. If his cavalry remained locked with

Kilpatrick’s, one of the Union infantry corps could show up in his rear. His

strategy was to wait for nightfall in hopes that he could pull out and find

another route. He did so, taking his men south in search of another way to link

up with Robert E. Lee. Surprisingly the aggressive Kilpatrick, perhaps still

believing Payne’s inflated numbers, did not pursue Stuart or even try to

maintain contact. He instead rested his men, satisfied that the Federals had

scored another victory over Stuart.[36]

Kilpatrick was ebullient in the conclusion of his battle report. “My loss is

trifling. I have gone into camp at Hanover. My command will be in readiness to

move again at daylight to-morrow morning. We have plenty of forage, the men are

in good spirits, and we don’t fear Stuart’s whole cavalry.[37]

Casualties

are somewhat hard to determine. Many battle reports were either lost or simply

not written up. In the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion there are

none from Custer’s Michigan Brigade or the Confederate side. Farnsworth’s

brigade listed the following losses.

5th

New York: 4 killed, 25 wounded, 10 missing

18th

Pennsylvania: 4 killed, 27 wounded, 50 missing

1st

Vermont: 1 wounded, 16 missing

1st

West Virginia: 2 killed, 2 wounded, 3 missing

Farnsworth

lost 144 men overall. The missing were probably among the 400 prisoners in

Stuart’s convoy. According to the Hanover Historical Society (I could only access

this information via Wikipedia unfortunately), the Federals lost 215 overall.

Confederate losses are even harder to nail down. In the aftermath of the battle

the Federals counted about 25 dead Confederates within Hanover itself and

captured about 75. This source is the 5th New York’s regimental

history. The Historical Society claims 117 overall. This would leave only 17

casualties in killed and wounded outside the town, for both Farnsworth’s charge

and Custer’s involvement. Obviously many Confederates were killed and wounded

outside the town as well. The regimental history likely exaggerated the numbers

of dead in town, or perhaps numbers determined by the Hanover Historical

Society undersold Stuart’s losses.[38]

Stuart’s

cavalry continued to search for Lee’s army. Their night march, following a

lengthy battle, was terrible. They were running low on feed and water for their

mules, and also dealt with the “unmitigated annoyance” of about 400 Federal

prisoners who further tasked their resources. They reached the town of Dover

expecting to find Jubal Early’s division, but it was not there. They then looked northwest to Carlisle where

there were supposed to be rations to alleviate their hunger. They instead found

entrenched Union militia. Stuart’s artillery shelled the town and burned the

barracks, but pressed no further. Finally a courier from Lee came telling him

to get to Gettysburg. Stuart’s horsemen went on a hard ride of 30 miles.[39]

Kilpatrick

would also arrive late at Gettysburg. Having failed to keep any eyes on Stuart,

he led his horsemen on a wandering search for where he supposed the enemy to

be. Finally orders came for Kilpatrick and his two brigades to go to

Gettysburg. This led to one brief skirmish on July 2 outside Hunterstown, where

Stuart was passing through. The 6th Michigan caught up with Wade Hampton’s

rear guard and surprised it. One trooper, James C. Parsons, actually got into a

personal gun duel with Hampton himself, his Spencer against a revolver. When

Parsons ran out of ammunition, he raised his hand to signal that he had to

reload. Hampton graciously gave him time to do so. Hampton did not suffer for

his chivalry. When Parsons raised his reloaded weapon, the cavalier fired first

and sent a ball into the trooper’s wrist. The wounded Parsons scurried into the

woods. Just then a mounted Union officer came at Hampton from behind with a

saber. He whacked the general on the back of the head with the flat of his

weapon. Thanks to his hat and thick mane of hair, Hampton was hurt but not

seriously injured and sent the horseman fleeing with a loud growl. Custer

arrived on the scene and rashly led a charge of 50 men (about all he had

available on the spot), despite his ability to call up reinforcements. The

Michiganders rode towards Hampton’s men with fierce yelling and then fell prey

to dismounted skirmishers. The horsemen retreated and Hampton held off Custer

with the aid of two artillery pieces from Ewell’s corps and they arrived at the

main battlefield late that afternoon. Though beaten in this encounter, Custer’s

Michigan brigade would gain prestige on the third day of Gettysburg’s battle.

While Pickett’s Charge struck the Union center at Cemetery Ridge, Custer and

other Union cavalrymen defeated Stuart in a field to the east. The Michigan

Brigade played a large role in this victory. Elon Farnsworth, situated by the

Round Tops on the Union’s southern left flank too would make his mark on the

battle. He unfortunately headed Kilpatrick’s ill-advised assault against well

defended Confederates in the battle’s waning moments, and himself was killed.[40]

The

Battle of Hanover, like most cavalry engagements, was a light battle, though

both sides had at least a few thousand men on hand. The battle deserves

recognition for destroying any chance Stuart had of linking up with Lee in a

timely manner. Furthermore, if he had gone through Hanover, he would have led

his men to Gettysburg. Depending on exactly when he got there he would have

linked up with General Richard Ewell’s 2nd Corps north of the town

or he would have run into General John Buford’s Federal cavalry. In the latter

scenario he would have been able to alert Lee. Then Lee could have either avoided

a battle there or perhaps sped things up and seized the critical heights there.

Of course there are countless ways things could have gone. An alternate Battle

of Gettysburg would see the Army of Northern Virginia in a more favorable

position, or Meade would have backed off and tried to coax Lee south to the

battleground he actually wanted at Pipe Creek.

What

did happen was that Stuart spent two more critical days wandering around the

Pennsylvania countryside. The absence of Stuart meant that the main Confederate

force marched blindly into a grand battle at Gettysburg. The Union got and

seized the initiative, fortifying the heights south of town. This forced the

Confederates to stretch their numerically inferior force around the defenders’

fishhook position and then, with Lee unwilling to disengage, make a series of

assaults that almost but never succeeded in scoring another victory for the

Army of Northern Virginia. The Battle of Hanover was one of many factors that

contributed to Lee’s first and perhaps only severe tactical defeat.

|

| The Hanover Monument |

Sources

Avery, James

Henry. Under Custer’s Command: The Civil

War Journal of James Henry Avery. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006.

Beale, Richard

L. T. History of the Ninth Virginia

Cavalry, in the War Between the States. Richmond: B.F. Johnson Publishing

Company, 1899.

Beaudry, Louis

Napoleon. Historic Records of the Fifth

New York Cavalry. Albany: S.R.

Gray, 1865.

Blackford,

William W. War Years with Jeb Stuart.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1945.

Editors of

Time-Life Books, Gettysburg: The

Confederate High Tide, (Time Life Books, 1985), 27-28, 72-73.

“Hanover

– First Phase of Fighting – June 30, 1863.” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/hanover-first-phase-fighting-june-30-1863

“Hanover

– Second Phase of Fighting – June 30, 1863.” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/hanover-second-phase-fighting-june-30-1863

Kidd, James H. Personal Recollections of a Cavalryman with

Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade in the Civil War. Ionia, Michigan:

Sentinel Printing Company, 1908.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/29608/29608-h/29608-h.htm#CHAPTER_XI

Longacre, Edward

G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical

Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June –

14 July 1863. Associated University Presses, Inc., 1986.

- - Custer and His

Wolverines: The Michigan Cavalry Brigade 1861-1865. Conshohocken:

Combined Publishing, 1997.

- - Gentleman and

Solider: A Biography of Wade Hampton III.

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

McClellan, Henry

B. I Rode with Jeb Stuart: The Life and

Campaigns of Major General J.E.B. Stuart. New York Da Capo Press, 1994

edition.

Publication

Committee of the Regimental Association. History

of the Eighteenth Regiment of Cavalry Pennsylvania Volunteers. Wynkoop

Hallenbeck Crawford co., 1909.

Sears, Stephen. Gettysburg. Mariner Books, 2004 edition.

Warner,

Ezra. Generals in Blue: Lives of the

Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1964.

Wittenberg, Eric

J. Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb

Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie, 2006.

[1] Editors of Time-Life Books, Gettysburg: The Confederate High Tide,

(Time Life Books, 1985), 27-28.

[2] Henry B.

McClellan, I Rode with Jeb Stuart: The

Life and Campaigns of Major General J.E.B. Stuart, (New York Da Capo Press,

1994 edition), 321-322.

[3] McClellan, I Rode with Jeb Stuart, 321-322.

[4] Editors of Time-Life

Books, Gettysburg: The Confederate High

Tide, 72-73; Sears, Gettysburg,

132.

[5] Akers, Year of Desperate Struggle: Jeb Stuart and

His Cavalry, from Gettysburg to Yellow Tavern, 1863-1864, (Oxford: Casemate

Publishers, 2015), 36; Blackford, War

Years, 225; Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s

Controversial Ride, 67.

[6] Sears, Gettysburg, 33.

[7] Ezra Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union

Commanders, (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1964), 148-149.

[8] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 70.

[9] Eric J.

Wittenberg, Plenty of Blame to Go Around:

Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. New York, (Savas Beatie,

2006), 85; Louis Napoleon Beaudry, Historic

Records of the Fifth New York Cavalry,

(Albany: S.R. Gray, 1865), 230.

[10] Edward

Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines: The

Michigan Cavalry Brigade 1861-1865, (Conshohocken: Combined Publishing,

1997), 128

[11] Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines, 131; James H.

Kidd, Personal Recollections of a

Cavalryman with Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade in the Civil War, (Ionia,

Michigan: Sentinel Printing Company, 1908)

[12] Edward

Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg: A

Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9

June – 14 July 1863, (Associated University Presses, Inc., 1986), 172.

[13] Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg, 173.

[14] Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg, 173; OR XXVII,

986, 1008; Publication Committee of the Regimental Association, History of the Eighteenth Regiment of

Cavalry Pennsylvania Volunteers, (Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford co., 1909),

77.

[15] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 68.

[16] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 80-81.

[17] Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg, 174-175;

Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial

Ride, 81-82.

[18] Richard L.T.

Beale, History of the Ninth Virginia

Cavalry, in the War Between the States, (Richmond: B.F. Johnson Publishing

Company, 1899), 82.

[19] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 86-88.

[20] OR XXVII, 1005,

1008-1009,1011; Beaudry, Fifth New York

Cavalry, 64; Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s

Controversial Ride, 83; Longacre, Cavalry

at Gettysburg, 175-176.

[21] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 85.

[22] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 86.

[23] OR XXVII, 1005,

1008-1009, 1011; Beaudry, Fifth New York,

64-65; Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg,

175; Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s

Controversial Ride, 84, 89-92.

[24] OR XXVII, 1005,

1008-1009, 1011; Longacre, Cavalry at

Gettysburg, 175-176; Wittenberg, Jeb

Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 92-95; Beaudry, Fifth New York, 65-66.

[25] Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg, 175-176;

Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines,

134; Akers, Year of Desperate Struggle,

38; Kidd, Personal Recollections;

Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier, 144.

[26] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 91-92;

Blackford, War Years, 225-226.

[27] McClellan, I Rode with Jeb Stuart, 328; Blackford, War Years, 226-227.

[28] Blackford, War Years, 227; Akers, Akers, Year of Desperate Struggle, 38-39;

Beale, Ninth Virginia Cavalry, 83.

[29] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 98-101.

[30] Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg, 176-177; Akers, Year of Desperate Struggle, 39; McClellan, I Rode with Jeb Stuart, 329; Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier, 144; “Hanover – Second Phase of Fighting – June 30, 1863.” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/hanover-second-phase-fighting-june-30-1863

[31] Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines, 133, 135; “Hanover

– Second Phase of Fighting – June 30, 1863.” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/hanover-second-phase-fighting-june-30-1863

[32] Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines, 135-137; Kidd, Personal Recollections.

[33] Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines, 137.

[34] Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines, 137-138;

James Henry Avery, Under Custer’s

Command: The Civil War Journal of James Henry Avery, (Washington, D.C.:

Potomac Books, 2006), 31-32.

[35] Wittenberg, Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride, 110.

[36] Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg, 178.

[37] OR XXVII, 987.

[38] OR XXVII, 1005,

1009, 1011-1012; Beaudry, Fifth New York,

65.

[39] Akers, Year of Desperate Struggle, 39-40;

Blackford, War Years, 228, Sears, Gettysburg, 153.

[40] Longacre, Cavalry at Gettysburg, 178, 178-179;

Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines,

140; Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier,

147-150.

No comments:

Post a Comment