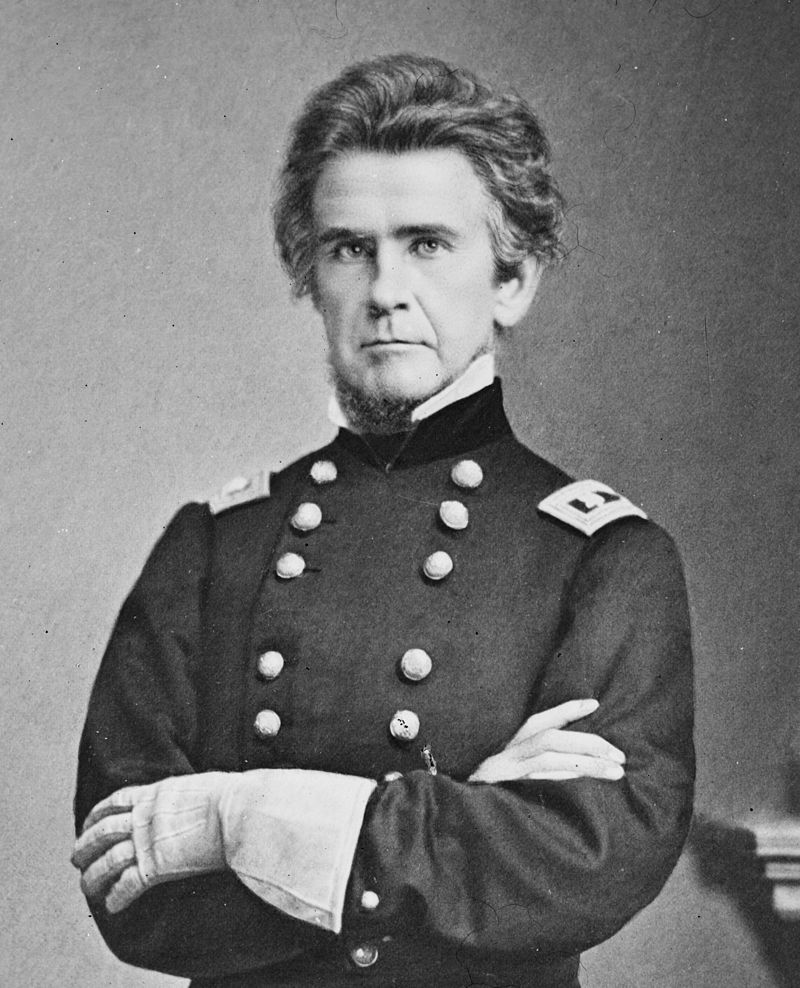

On May 2, 1862, a brigade of Union soldiers descended on Athens, a small town and transportation hub in northern Alabama. What ensued was one of the earliest incidents of hard war against civilians, at a time when Union military policy stressed policies that would win ostensibly reluctant Secessionists back into the Union. The man at the center of this controversy was Colonel John Turchin, known by his detractors as the Mad Cossack.

The Mad Cossack

John Basil Turchin was the Americanized name of Ivan Vasilyevich Turchaninov. Turchaninov was born in the Province of the Don (the historical domain of the Cossacks) on January 30, 1822. His father was a major in the Imperial Russian Army and a lower-ranking noble. Ivan thus got into a good school, where he excelled. At the age of 14 he followed his father into the military, rising to colonel of the Imperial Guard in 1841. In 1849 he helped quash a revolution in Hungary. One historian notes that the soldiers’ large scale theft of food from the peasants was approved of as initiative by their commanders, as they were having trouble bringing their own stores of food up to the front. This might have played a role in Turchin’s mindset 30 years later.

During the Crimean War (1853-1856) he first earned a position on the personal staff of crown prince Alexander and then established defenses along the Finnish coast (Finland was at this time part of the Russian Empire). In 1856 Turchaninov married Nedezhda Lvova, an aristocrat’s daughter he had met in Poland. Around this time Turchaninov began to chafe at the military system in Russia. It promoted men through the ranks by nature of their birth and connections rather than merit. It also got in the way of much needed reforms. As a competent officer unable to rise any higher because of his comparatively modest background, Ivan was especially frustrated by the Russian Imperial order. He and Nedezhda, both liberal Russians, decided to move away from their homeland and its firm class system. They sought life in the United States. There the ex-soldier gained his Anglicized name while running a farm in New York. Once he and his wife learned English they moved to Chicago where he used his military experience to become an engineer.[1]

Turchin

was an enthusiastic supporter of the Union as envisioned by the North, seeing

the South and its aristocracy as a counterpart of the Russia he had grown

disillusioned with. Once the Civil War started, Turchin’s experience in the

Russian Army and Crimean War naturally won him a high rank as Colonel of the 19th

Illinois. Many of the men in this regiment had been trained in the prewar

militia by Elmer Ellsworth, the youthful Zouave officer who had been killed

while trying to take down a Confederate flag at a Virginia Secessionist’s home.

The men felt a strong desire for revenge alongside their commitment to the

Union.

Acquiring

command of this regiment, Turchin found himself overseeing a mix of

well-trained militia officers and incompetent political appointments. Turchin’s

background made him an excellent drillmaster.

However he also had little regard for the private property of civilians.

In 1861 his regiment served under General John Pope in Missouri. He frequently

took foodstuffs and other property from civilians he deemed disloyal to the

Union, which could potentially include neutral people. Though he butted heads

with his superiors over this, he and his men somehow never faced any

repercussions over this. Helping him was a shift in military policy that

allowed property to be seized out of military necessity.

The

US government sought conciliation in the early stages of the war and often

urged the military to respect the possessions of Southerners, even protecting

their property against fellow soldiers. If the Army did take property, officers

were to ensure that it was done out of military necessity and that the names of

the previous owners were recorded for later reimbursement Turchin believed

these rules were ridiculous in a war and turned a blind eye towards his men

when it came to dealing with civilians. In fact he encouraged the seizure of

enemy civilian property beyond the prescribed limits. Among these were the

slaves. Turchin was among the first Union commanders to emancipate them in

opposition to official policy. Throughout the early stages of the war he

insisted that liberating slaves was the proper strategy, because they had every

reason to supply the Union armies with vital information. Less heartwarming

would be his men’s attitude towards property in Athens. [2]

Turchin’s

wife, now Nadine Turchin, traveled with the regiment despite US Army

regulations prohibiting wives to accompany their soldier husbands. The men

liked their commander, but loved Nadine. She assisted with nursing and

emotional comfort, and the soldiers “respected, believed in, and came to love

her for her bravery, gentleness, and constant care of the sick and wounded.” On

campaign she would ride on an ambulance. She also carried a revolver and dagger

on her in case she would have to get dirty alongside the boys.[3]

Northern Alabama

By February Colonel Turchin had risen to brigade command in General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. In addition to the 19th Illinois, he now also led the 24th Illinois, 37th Indiana, and 18th Ohio. He won over the 37th Indiana by reining in their unpopular commander Colonel George Hazzard. Hazzard was very rigid and oversensitive to criticism. He even nearly attacked Turchin when he misunderstood an order. The Mad Cossack soon had him arrested and then removed from command, leaving behind a loyal regiment. Later that month Turchin’s brigade participated in eastern Kentucky operations. In his first month of command Turchin raised the attention of his peers by allowing his men to “gut” the homes around them, depriving Kentuckians of their private property beyond reasonable limits of military necessity.[4]

Following

up early Union successes in Kentucky and Tennessee, Turchin led his brigade

into northern Alabama at the beginning of May 1862. His divisional superior was

General George Mitchel, a West Point graduate and respected scientists and

engineer in peace time. Turchin’s task was to secure the railroads and bridges

around Athens, a transportation hub. The Nashville & Decatur Railroad ran

nearby on the Elk River and Limestone Creek railroad bridges. To the south were

the town of Decatur and the railway junction of the Memphis & Charlestown.

The town of Athens itself had just 887 inhabitants, 338 of them slaves. Of the

white inhabitants, most were pro-Confederate or apathetic to the war, wishing

only to be left alone. As a former engineer in the Russian Imperial Army,

Turchin was well suited to the task of maintaining rail service for the Union

Army.[5]

The

Confederates were not idle in the face of this occupation. Confederate

guerillas raided Federal lines of supply and communication, specifically

targeting bridges and railroads. On one foray they captured and hung a picket.

South of Athens Colonel John S. Scott sought to draw away Federal forces

through disinformation. He let it slip to an informer that 15,000 Confederates

were gearing up for an assault on Tuscumbia, 50 miles to the west. In response

Turchin moved in that direction to Decatur. He left behind the 18th

Ohio under Colonel Timothy Stanley to maintain control of the railroads.[6]

The

18th Ohio organized its occupation of Athens. Colonel Stanley and

his staff set up camp at the courthouse square. Company E set up at the

Limestone Creek railroad bridge. Company I went north to Pulaski, Tennessee.

300 men set up a tent town at Athens’ fairgrounds racetrack. For the first

couple days of occupation the Ohioans behaved themselves and the Athenians were

glad to have “such a quiet and orderly set.”[7]

With Turchin gone and the 18th Ohio spread out in and around Athens,

Scott launched an attack owith his 19th Louisiana Cavalry on April

29.[8]

The

19th Louisiana struck the pickets guarding the bridges on the Athens

and Decatur road. Scott only had 112 mounted men and a battery of howitzers. The

Ohioans drove back the cavalry, only for the Confederates to open up with their

three howitzers. Fearing that the enemy was much larger than he had initially

thought, Stanley ordered all of his wagons to leave, abandoning his tents and

other supplies. General Mitchel happened to be riding into town on a train and sent

a black man to inform Stanley he should expect reinforcements. Mitchel then

took the train to a telegraph station and wired for the additional men.[9]

The

Louisianans were thrilled to learn that the Federals had “left their tents

standing, a considerable quantity of their commissary stores, all camp

equipage, and about 150 stand of arms; also some ammunition.” Scott reported 1

man killed and 3 wounded. He exaggerated Federal losses at 200 killed and

wounded.[10] The

18th Ohio reached Huntsville in an infuriated state. They claimed

that the citizens had colluded with Scott to drive them out and then rubbed in

their defeat with jeers and insults. Some had even fired at them from the

rooftops. There is likely some truth in these charges, but the Ohioans were

exaggerating the truth in light of their defeat. The initial reports of Colonel

Stanley and Lieutenant-Colonel Josiah Givens mentioned shouting and

insults, but nothing about civilian attacks. In fact, many of the armed

“civilians” were actually Confederates soldiers who had been unable to procure

proper uniforms.[11]

The

atmosphere worsened as guerillas waged war on the Federal invaders, targeting

their supply lines with Huntsville, Alabama. Saboteurs drove off a guard,

killing 2 and wounding 5, and destroyed a train full of rations on the

Limestone Creek Bridge, starting by sawing the beams. A train full of soldiers

came and crashed, trapping two soldiers in a car. Then the car went on fire.

One of the soldiers aboard found himself caught between the tender and engine,

and was “actually roasted alive” in the presence of the guerillas. The

perpetrators further promised to kill any slave who tried to rescue the burning

man. Mitchel ordered Turchin to reconquer Athens, and was heard to say in the

presence of the 19th Illinois, “don’t leave a grease spot.”[12]

The

Federals arrived there on May 2 to find that Scott had departed. The

Confederates had destroyed all captured goods they had could not carry and

after capturing about 20 Union foragers, fled in the night. Mitchel sent

cavalry in pursuit. Around 10 AM they struck the retreating Louisianans on Elk

River while they were still crossing. The Confederates beat them back, having

lost 4 men killed and 5 wounded throughout their retreat. Scott lamented in his

report, “I am out of ammunition and my horses are very much jaded.” This was

very unfortunate for the town’s citizenry.[13]

The Sacking

Though they found no Confederate soldiers, army or guerilla, the Federals were still in heat. What ensued was a battle against civilians. The following incidents were collected for testimony against Turchin in a court-martial. One band of looters went to the office of R.C. David and took for themselves $1,000 dollars and clothes. They also savaged “a stock of books, among which was a lot of fine Bibles and Testaments.” They tore out the pages, mutilated the covers, and kicked and trampled the remains. Another squad entered the home of the Malones, currently occupied by “two females” (ages and relations to each other not specified). They took all the money, jewelry, plates, and ornaments they could find and destroyed all the furniture.[14]

They

were not the only Malones to suffer. Throughout the day soldiers from

Edgarton’s Battery and the 37th Indiana went to the house of Thomas

S. Malone, taking or destroying $4,500 of property. They made an effort to take

or destroy all the papers in his desk. These same men “plundered the drug store

of William D. Allen, destroying completely a set of surgical, obstetrical, and

dental instruments, or carrying them away.” John F. Malone also suffered a home

invasion. The soldiers destroyed all the locks to get in and proceeded to check

and plunder everything with a drawer. Their acquisitions included clothes, jewelry,

silverware, and a gold watch and chain. Throughout this they verbally abused John Malone’s wife and daughters. Not content to just defile his home, they

decided to take up residence at the slave quarters. According to the

court-martial the male slaves assisted them in roaming the “surrounding

country to plunder and pillage.” Also the soldiers were said to have engaged in

“debauching the [slave] females.” If this suggests rape, then their black co-plunderers

may have been pressured into assisting them. There are not enough details to

get a clear picture of what the relationship between the white Union soldiers

and Malone’s slaves were.[15]

There

were plenty more targets. $3,000 worth of property was taken from the store of

Madison Thompson. Not content with just attacking the store, the soldiers also

went into the adjoining stable and took all the horsefeed. The scholarly J.F.

Lowell was distraught to learn that his office was broken into. The looters

took his microscope, “geological specimens,” surgical tools, and books. The

same pattern of behavior occurred at “the business houses of Samuel Tanner,

Jr.,” the houses of Mrs. Hollinsworth and J.A. Cox, George Peck and John

Turrentine’s stores, and the P. Tanner & Sons’ brick store. Of course they also targeted D.H. Friend’s

silversmith shop and jewelry store. Officers were just as culpable in the

looting. Captain Edgarton, an artillery officer, ordered many of the break-ins,

and Lieutenant Berwick participated in the theft of “bedding, furniture, and

wearing apparel.”[16]

Captain

Mihalotzy of the 24th Illinois spearheaded the takeover of the Jones

House. He ‘behaved rudely and coarsely to the ladies of the family” before

placing two companies of men in their home. Captain Edgarton arrived later and

stationed his men in the parlor rooms. The artillerists went to looting the

home, tearing up the furniture and carpeting. They chopped up a piano with an

axe and cut bacon on the carpet. When they went to bed that night they kept

their muddy boots on, spoiling the sheets.[17]

Another

group of Federals broke into the house of Milly Ann Clayton, a 38 year old

widow. Operating on the story that the civilians fired at the retreating

Ohioans days earlier, they demanded that Clayton hand over the weapons in here

house, to which she “told them there were none.” The soldiers, one pulling out

a revolver, then called her a “God damn liar” and a “God damn bitch.”

Threatened she revealed that there were indeed two guns in her home. Inside,

they “opened all the trunks, drawers, and boxes of every description, and

taking out the contents thereof, consisted of wearing apparel and bed-clothes,

destroyed spoiled, or carried away the same.”[18]

Some

of the men who looted Friend’s jewelry store split off and entered the home of

R.S. Irwin. They ordered his wife to make dinner for them. She did so with the

assistance of her black servant girl. As they did so the unwanted house guests

“made the most indecent and beastly propositions” to the black girl. When she

left the room, they followed her and continued to make crude advances. There is

no evidence that they followed through with their wishes. [19]

Turchin

did not force himself onto any of the private homes. Instead he stayed in a

hotel for a week. One of the charges against him was that he did not pay the

landlord for using his building. One soldier of the 18th Ohio

claimed that he had sat on the front of the courthouse, watching his men run

wild. The other story of his reaction to the ongoing plunder, involving an

attempt to represent a Russian accent is most likely apocryphal. After waking

up from his hotel bed he told a lieutenant, “I dink it ish dime to shtop dis

tam billaging.” The lieutenant replied, “Oh, no, Colonel, the boys are not yet

half done jerking.” “Ish dot so? Den I schlep for half an hour longer.”[20]

One

rationale for the escalating looting was the discovery of 18th Ohio

supplies. After the regiment’s flight the civilians had helped themselves to

abandoned knapsacks and other gear. This was used to justify the thorough

plundering of homes and businesses. Those who took clothing put them on,

sometimes in purposefully gaudy fashion. As for the obsession with stealing or

destroying books, the historian George Bradley theorizes that this was “a handy

sort of revenge against Southern aristocracy and learning.”[21]

For

the next several days Turchin’s brigade managed Athens with a heavy hand. They

impressed slaves and horses, using the latter to mount men for raids and forays

into the countryside. Nadine took a lady’s horse and used it for her own daily

rides. The soldiers continued to steal valuables they had missed on May 2, but

grew more obsessed with taking food. They fanned into the countryside to take

from outlying homes.[22]

On

May 3 a sexual misdeed occurred at the home of Mrs. Charlotte Hine (or Haines),

a widow. Several soldiers entered and one, Ayer Bowers, went after Hine’s slave

girl in the kitchen. He told her to drop a baby she was carrying and have sex

with him. The girl was frightened and obeyed. Bowers raped her right in front

of Mrs. Hine. The group then plundered the kitchen and carried “off all the

pictures and ornaments they could lay their hands on.”[23]

Fallout

|

| General Ormsby Mitchel |

The Sack of Athens was so thorough that it was inevitable Turchin’s superiors would hear of it. General Mitchel, who either thought his subordinate went too far or was trying to save his own career, was none too pleased with his following reports. Mitchel personally visited Athens and interviewed its citizens. From them he was sure that Turchin’s brigade had indeed committed multiple crimes. The black girl’s mistress, Miss Clayton, backed up the charge that she had been raped. Mitchel gathered all his main officers and “in the sternest language I could employ” harangued them for what had occurred.[24]

On

May 7, General Mitchel demanded that Turchin punish his men. His specific

instructions were to “Shave the heads of the offenders, brand them thieves, and

drive them out of camp.” Over a week later he demanded that he “report whether

any, and, if any, what, excesses and depredations on private property were

committed by the troops under your command.”[25]

Mitchel next ordered that all troops be removed from private homes, and all

baggage inspected thoroughly for stolen property. “I would prefer to hear that

you had fought a battle and been defeated in a fair fight than to learn that

your soldiers have degenerated into robbers and plunderers.”[26]

Mitchel

also had to cover his own reputation. He wrote to Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary

of War, that he did his full “duty in repressing pillaging and plundering by

the troops under my command.” He had extensive records showing that he ordered

all subordinates to control their men, that convicted and suspended all

offenders, and that he had all the participants of the Sack of Athens

thoroughly searched for stolen property.[27]

Mitchel also addressed his recent entry into the cotton business. Careful not

to be accused of corruption, he informed Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase

and General Don Buell that he undertook this venture to raise money so he could

pay to get the trains running and had all the proceeds sent to the US Treasury.

Mitchel’s son in law, W.B. Hook, traveled to New York to find buyers. He did

so, but was temporarily captured on the way back by John Hunt Morgan’s

guerillas. The frightened Hook returned to New York, failing to complete the

transaction.[28]

At

this point of the war, little over a year in, the Sack of Athens was shocking. It

was inevitable that Turchin would face a court-martial. From July 5-20, the event

was held at Athens. The Mad Cossack faced the following charges:

16

of the 19 summoned witnesses were citizens of Athens. Turchin objected on the

grounds that they would be too biased against him and demanded that they be

made to state under oath whether they were Unionists or Confederates. The court

denied this demand. Northerners who were aware of the trial were outraged that

Secessionists would be allowed to testify against a Union officer. Turchin had

support from his officers, who testified that the atrocities were exaggerated

and that the Russian had tried to restrain his men. Others pointed out that

General Mitchel had incentivized the sack of Athens with his phrase “don’t

leave a grease spot.”[30]

Turchin

pled not guilty on all charges save the fourth specification to the third

charge. This specification had nothing to do with the sack, but the presence of

his wife contrary to regulations. Turchin also showed no distress at the hatred

white Southerners displayed against him. He said it was “my best recommendation

as a loyal officer.” Still, the court found him guilty, with the caveat that

because of “exciting circumstances” he should be given a lenient punishment.

General Buell, the commander of the Army of the Ohio and much more moderate in

his politics than Turchin, would have none of this:

The question is not whether private

property may be used for the public service, for that is proper whenever the

public interest demands it. It should then be done by authority and in an

orderly way, but the wanton and unlawful indulgence of individuals in acts of

plunder and outrage is a different matter, tending to the demoralization of the

troops and the destruction of their efficiency.

He

ordered the Mad Cossack out of the army.[31]

Though convicted, Turchin became a popular figure in the North, especially

among those who criticized Buell for being too soft on

the Confederacy.[32] Nadine

Turchin was certainly not going to take her husband’s expulsion lying down. She

went to Washington D.C. and personally visited President Abraham Lincoln to

overturn her spouse’s conviction. She must have impressed the chief executive

or else done a good job at tugging on his heartstrings, because he not only

restored the Mad Cossack to his command, but promoted him to brigadier-general

on August 5.[33]

Rescued

by his wife, Turchin saw further service. In September of 1863 he fought well

at Chickamauga and earned the nickname “The Russian Thunderbolt.” Two months

later he was among the first officers to lead his regiment to the top of

Missionary Ridge outside Chattanooga. In the midst of the following Atlanta Campaign,

a severe case of heatstroke forced him to resign. After the war he would

establish a Polish community at Radom, Illinois. He also wrote a book about his

experiences in the Civil War. However, it was entirely focused on Chickamauga

(the title of his work), where he achieved positive fame. It’s also more of a

battle history with a first-person flavor. The citizens of Athens finally got

their justice in 1901, when he suffered a heart stroke that drove him mad. He

was sent to the Southern Hospital for the Insane in Anna, Illinois, and soon died

on June 18.[34]

In Perspective

The Sack of Athens was notorious, but became a relatively obscure event of the Civil War. The mass plunder of a single town, even with one or two rapes involved, could not measure up to the more frequent destruction visited upon the South later in the war, or any of the large scale massacres involving irregular warfare and racially charged encounters between Confederate and black Federal troops. The event also occurred in what many consider a sideshow theater. Turchin’s method of waging war was prescient of later Union military policy. He held the belief that the Union Army should not hold back in suppressing the Confederacy. After many frustrating failures and setbacks, as well as encounters with a resistant and resilient Secessionist populace, other Union leaders adopted the same attitude and carried it out, if with more emphasis on military necessity than petty revenge.

Sources

Bradley, George

C. From Conciliation to Conquest: The

Sack of Athens and the Court-Martial of Colonel John B. Turchin.

Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

Buhk, Tobin T. True Crime in the Civil War: Cases of

Murder, Treason, Counterfeiting, Massacre, Plunder, & Abuse.

Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2012.

Casstevens.

Frances Harding. Tales from the North and

the South: Twenty-Four Remarkable People and Events of the Civil War.

Jefferson: McFarland & Co. 2007.

Turchin,

John B. Chickamauga. Chicago: Fergus

Printing Company, 1888.

United States. The War of

the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies Vol. X parts 1 and 2.

Washington D.C. 1884.

Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union

Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1964.

[1] Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union

Commanders, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1964), 511; George C.

Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest:

The Sack of Athens and the Court-Martial of Colonel John B. Turchin, (Tuscaloosa:

University of Alabama Press, 2006), 18-19, 23-24; Tobin T. Bukh, True Crime in the Civil War: Cases of

Murder, Treason, Counterfeiting, Massacre, Plunder, & Abuse, (Mechanicsburg:

Stackpole Books, 2012), 46; Frances Harding Casstevens, Tales from the North and the South: Twenty-Four Remarkable People and

Events of the Civil War, (Jefferson: McFarland & Co. 2007), 97-98.

[2] Warner, Generals in Blue, 511; Bukh, True Crime, 46-48, 55; Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest, 40-41,

48-53; John B. Turchin, Chickamauga,

(Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1888), 5-6.

[3] Casstevens, Tales from the North and the South, 98-99.

[4] Bukh, True Crime, 48; Bradley, From

Conciliation to Conquest, 62, 65-66.

[5] Bukh, True Crime, 48; Bradley, From

Conciliation to Conquest, 100-102.

[6] Casstevens, Tales from the North and the South, 101; Bukh, True Crime, 48.

[7] Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest, 103-104.

[8] Bukh, True Crime, 48.

[9] United States, The War of

the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies Vol. X part 1 (Washington

D.C. 1884), 876-877.

[10] OR X, part 1, 787.

[11] Bukh, True Crime, 48-49; Casstevens, Tales from the North and the South, 101;

Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest,

105.

[12] OR X, part 1, 877, part 2, 291;

Bukh, True Crime, 49.

[13] OR X, part 1, 877, 879.

[14] OR XVI, part 2, 274.

[15] OR XVI, part 2, 274.

[16] OR XVI, part 2, 274-275.

[17] OR XVI, part 2, 275.

[18] OR XVI, part 2, 273-274;

Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest,

110-111.

[19] OR XVI, part 2, 274-275.

[20] OR XVI, part 2, 275; Bukh, True Crime, 50, 54.

[21] Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest, 111-112.

[22] Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest, 118-121.

[23] Bradley, From Conciliation to Conquest, 121; Bukh, True Crime, 50.

[24] OR X, part 2, 290-291.

[25] OR X, part 2, 294.

[26] OR X, part 2, 295.

[27] OR X, part 2, 290.

[28] OR X, part 2, 291-292.

[29] OR XVI, part 2, 273, 275-276.

[30] Bukh, True Crime, 53-54.

[31] OR XVI, part 2, 276-277; Bukh, True Crime, 55.

[32] Bukh, True Crime, 56.

[33] Casstevens, Tales from the North and the South, 101.

[34] Warner, Generals in Blue, 511-512; Buhk, True Crime, 57.

No comments:

Post a Comment