Neutral

Hopes

War among the whites was not supposed to happen in

Sub-Saharan Africa. The Scramble for Africa and other colonial ventures had

been morally justified on the idea of transmitting European civilization to the

unenlightened (“White Man’s Burden”). The whites had to set an example by

showing they had moved beyond fighting each other. There were another dimension

to this ideological reasoning. One was that Europe itself was hoping never to

repeat the widespread conflagration of earlier coalition wars, the Napoleonic

Wars serving as the most recent example. Europeans had managed to avoid any

such conflicts for about a century. What wars there were between the nations

included ones that were quick (Franco-Prussian War) or limited in its scope

(Crimean War). Thus Europe hoped to prevent any escalation of competing

imperial interests into a repeat of earlier disasters.

By not allowing blacks to see white kill white, the Europeans

in the colonies were primarily serving their own self-interests. After all,

they were perfectly willing to send blacks to kill other blacks. What they

realized was that if the supposedly superior whites began to kill each other,

it would undermine the image they had cultivated for themselves. Even worse,

such a war in the colonies might require the use of black troops against

whites, further undermining the hierarchy of race. Thus far the only

inter-white conflicts in Africa had occurred between the British Empire and the

Boers in Southern Africa, and these were not between the imperial powers, but

between just one of them and a defiant group of colonists. It was furthermore

restricted to only one part of Africa. World War I would be the true violation

of colonial neutrality.

An agreement of neutrality within the colonies was expressed

in the Congo Act of 1885. This act, agreed upon at the 1884-1885 Berlin

Conference, stipulated that in the case of any war between the colonial powers

within Europe, the colonies themselves would stay neutral. This would protect European

hegemony and power in Africa and allow it to continue in the aftermath. Many

colonial officials and settlers clung to the hope that the Congo Act would

avert war in Africa, but others saw it in a more realistic light. One stated

that it remained effective insofar that it had not yet been tested. Indeed, as

war clouds loomed, many in East Africa were planning to violate the Congo Act

or at least take preparations such an eventuality. One was a Prussian

officer, Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who set foot on East

Africa in at the end of 1913.

Lettow-Vorbeck:

Guerrilla or Bush-Fighter?

|

Lettow-Vorbeck’s task was to head East Africa’s Schutztruppe.

He had about 5,000 men under his command, roughly half of them German and the

other half Askari. During his initial

tour, he concluded that preparations had to be made for a war. While East

Africa would be a sideshow, he believed he could pin down British resources and

circumvent their use against the homeland. He militarized the police force to

extend his force to a still-small but much larger 14,000 men, 3,000 German and

11,000 Askari. Such a small force called for new tactics, and he took a page

out of the natives’ book.

Lettow-Vorbeck was liberal-minded when it came to other

cultures. This was first evidenced in China in 1900-1901. He was part of a force tasked with

relieving the besieged defenders of the embassies in Beijing during the Boxer

Rebellion. Though he arrived too late for the main show, he still saw some

limited action, but more importantly he displayed a quality that would serve

him well in Africa.

He exhibited a curiosity with foreign cultures, eager to learn how they

functioned, and along with that an ability to build friendly, more equitable

relations with non-whites. He helped put down the rebellions in German

South-West Africa, though it is difficult to say how he felt about the extreme

counter-measures used to repress the natives. What is known is that, like many

other German officers, he was impressed by the enemy’s fighting style and kept

notes.

Touring

German East Africa, Lettow-Vorbeck formed a strategy in his mind. He concluded that with his small force a defensive

posture was futile. German East Africa was roughly as large as Germany itself

and there were too many avenues for invasion. Instead he believed an aggressive

campaign would work, provided that the outnumbered Schutztruppe did not

disperse itself too far, kept on the move, and hit the enemy at “sensitive”

points. Hitting sensitive points would draw the enemy to pursue him, preventing

them from solidifying a conquest of the colony. In short, Lettow-Vorbeck sought

a hit-and-run war. In preparation he had caches of food and other supplies set

up all across the colony. This would enable him to move back and forth across

the colony without losing steam, provided he had an extensive carrier system.

Carrier systems, or porterage, saw columns of African

laborers carry the goods and supplies of whoever was employing them. The lack

of good roads for draft animals required these long lines of people and the

work was often miserable. It had first been used within the Arab slave trade,

when abducted peoples would be forced to carry other goods along with

themselves. While blasting the slave trade, Europeans found it necessary to

adopt the carrier system. Many strove to make it more humane while others

treated the porters poorly. As war loomed, there were still few railroads, or

roads in general, to use motorized vehicles. Draft animals had their use, but

were susceptible to a myriad of local diseases, mainly from the tsetse flies.

Human labor was still required for logistics, especially in a war of movement.

With Prussian efficiency, the Germans came up with an altered system of porterage.

Hundreds of thousands of Africans were employed in this system. Many were

temporary carriers who only had to transport supplies up to a certain distance.

They would then pass off supplies to other temporary carriers or to ones

permanently attached to Schutztruppe forces. This system promised to prevent

overwork, but faced serious strain as the war went on and supply lines

stretched.

Lettow-Vorbeck has been labeled a guerrilla fighter by many

writers.

They see his war of movement as a precursor to future Cold War conflicts across

tropical regions. Edwin Hoyt, author of Guerrilla,

went so far as to write that he was “the most successful guerrilla leader in

world history, and that his record has never even been approached by any

others, in terms of impact on his enemies, in terms of survival in the field

with no sources of supply for months on end, in terms of managing a racially

mixed fighting force with enormous skill, in terms of courage its and heroism,

and finally in terms of superb generalship that kept his enemies almost

constantly guessing”. High praise indeed, but not quite accurate.

While

it is true that Lettow-Vorbeck’s style of fighting was unconventional by

European standards, it cannot accurately be labeled as guerrilla-fighting. In

fact, he had merely merged two conventional forms together. It was traditional

German Bewegungskrieg (“War of

Movement”) mixed in with African bush-fighting. Bewegungskrieg was Prussia’s answer to its specific strategic

location in Europe. Prussia was usually surrounded by many hostile enemies, and

did not have the manpower and resources to conduct a protracted war. Its leader

Frederick the Great had come up with a strategy of swift movement. His army

would consolidate and strike swift and hard, aiming for a knockout blow and

quick victory. This kept Prussia alive during the Seven Years’ War (Bewegungskrieg explains how in World War

II Germany scored a smashing victory in its first battle with each foe).

However, a decisive early blow would be impossible in East Africa. Bewegungskrieg would be effective in a

limited tactical but not strategic sense. The Schutztruppe would have to keep

the fight going and hope for a favorable conclusion in Europe. This was where

the conventional African form of bush-fighting would come in handy. Filled with

dense jungles, stretches of infertile land, and stretches of hills, and also

still undeveloped by European standards, East Africa was not conducive to

massive armies and their required logistics. Already stuck with a small army,

Lettow-Vorbeck had no trouble adjusting. He would also adopt the hit-and-run

style of bush fighting, and his majority-native force would prove excellent for

this. Just as the Herero, Nama, and Maji-Maji participants had dogged German

colonial troops, the Schutztruppe would dog the Entente forces.

Lettow-Vorbeck's army also did not follow many of the requirements

of a guerrilla force. His men stayed in uniform and followed a traditional

military structure. They did not blend in with the civilian population. They did live

off the land with aid from the civilian populace, but the local African peoples

were not politicized, at least not in the name of the German Empire. They

supported the Schutztruppe for a myriad of reasons ranging from a dislike of

one of the Entente powers to the threat of force. In fact, at several points

the Schutztruppe found itself fighting natives who were independent of the Entente forces. Many

participants in the Maji-Maji Rebellion were still too subdued and unarmed to

defy the Germans, but those that had managed to hold onto an arsenal took action.

The Wahehe, survivors of the Rebellion, harassed German columns when

they passed through their land. Echoing earlier reprisals, Germans hung any

Wahehe men who fell into their hands. Thus the Schutztruppe was still a

colonial force of the occupiers rather than a guerrilla resistance.

Neutrality

Ends

|

| If not for the war, Heinrich Schnee might have been remembered as one of the better colonial administrators. Instead his arguments with Lettow-Vorbeck made him unpopular with military history enthusiasts. His later association with the Nazi party would also soil his reputation. |

War

finally broke out in Europe. On June 28, 1914, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and

his wife Sophie were assassinated in the Bosnian city of Sarajevo by the Serbian Black Hand. When the Serbian

government refused to cooperate in punishing the culprits, the Austro-Hungarian

Empire declared war. What follows next is a simplification of what was really the last steps of a mind-boggingly complex series of events. Russia rushed to Serbia’s aid and Germany to

Austria-Hungary’s. France fulfilled a treaty obligation by joining Russia, and

Britain joined this alliance as well when Germany violated Belgian neutrality.

By August the greatest war yet seen by man had begun. In German East Africa

Schnee ordered that no provocative moves be made by the colony’s military. He

was not the only one who sought the Congo Act’s promised neutrality. To the

north in British East Africa, many settlers scoffed at the notion of fighting

in Africa to win a war back in Europe. Aside from not wanting to risk their

lives, there were economic concerns. A few months of service away from their

settlements could end with their untended farms turning to nothing. Yet other

settlers were eager to prove their bravery and patriotism and signed up.

There

were too many patriots and opportunists for neutrality to succeed. Some of the

first shots of the war were fired in German Togoland, which was rapidly

conquered by an Anglo-French force. On August 4, 1914, the day war was

officially declared, the British made their first moves on East Africa and

seized several small outposts. The first major action occurred on August 8,

when the British cruisers HMS Astraea

and HMS Pegasus steamed towards Dar

es Salaam and bombarded the port. They demanded that all ports be declared open

cities. Schnee, still hoping to avoid a devastating war in his colony,

acquiesced and Lettow-Vorbeck grudgingly withdrew his forces from Dar es

Salaam. Though forced to give up defending the port, he made his first

audacious move. He crossed the northern border and dispersed the tiny force

guarding the town of Taveta (in present-day Kenya). His force became the first

and only German one to take British soil in the entire war. He followed up his

initial success by digging deeper along the Uganda railway into British East

Africa.

His

first campaign was soon beset by difficulties. He noted that the “supply of a

single company in the conditions” or East Africa “required about the same

consideration as would a division in Germany”. Coming to the rescue was Major

General Kurt Wahle, who just so happened to be on a vacation visiting his son when the war started.

Despite far outranking Lettow-Vorbeck, he quickly offered his services as a

subordinate and did an effective job organizing the Schutztruppe’s logistics.

As for the conclusion of the campaign, the Schutztruppe found the King’s

African Rifles, consisting mostly of native black troops, to be a match for

them. While the Schutztruppe and KAR traded victories in small skirmishes, the British took further measures to deter this invasion. They put heavy

armor on two of their trains and had them run up and down the railway to ward

off raids. A force of 4,000 Indians under Brigadier General James Marshall

Steward landed at Mombasa. Lettow-Vorbeck now found himself outnumbered two to

one.

Lake

Victoria also saw action. It began with the British steamer Winifred and the German tugboat Muansa. The Muansa threatened the British lake port of Kisumu and Winifred steamed out to confront her.

The following firefight was intense and Muansa

inflicted heavy casualties on the Winifred’s

deck with its machine guns. The crew of the Winifred

struggled to get their best weapon, a Hotchkiss gun, in a good clear position

to blast the Muansa. A railing

blocked the barrel, so they hastily erected a mount so they could fire over it.

The mount did not stand up when the gun fired and it fell apart. Then the

gunners painstakingly sawed off part of the railing. By the time they did so

the Muansa had retreated. The

following day a force of KAR troops and East African Mounted Rifles landed to

take out a nearby Schutztruppe post. The Schutztruppe Askaris, despite their

surprise, put up an effective fire. As with Lettow-Vorbeck’s raid into British

East Africa, the native KAR troops proved their worth. Sighting the smoke

issued by the Schutztruppe’s outdated rifles, they were able inflict heavy

casualties, forcing a withdrawal and gaining a victory. Despite their effective

performance on all fronts, the black soldiers in the KAR would be disregarded for much of the

East African campaign by prejudiced officers. By refusing to acknowledge the

benefits of employing native soldiers, these officers would hamstring their own

efforts.

The Konigsberg’s Run Begins

|

What

garnered the most attention at the time was the beginning of the 15-month game

of cat and mouse with the German light cruiser SMS Konigsberg. The Konigsberg,

completed and launched in 1905, was one of the prizes of the expanding Germany

navy. It had escorted the Kaiser’s yacht on several occasions. It had been sent

on a two-year tour of the Indian Ocean in an effort to bolster German colonial

prestige as well as to assure the colonists that they had naval protection,

though against the natives and Arab pirates rather than the British Royal Navy.

Currently north of German East Africa, it received word of the outbreak of war

on August 5. Its captain was Maximilien Looff. Looff had initially enjoyed his

tour, often going ashore to hunt big game. But as tensions escalated in Europe,

he found himself barraged by instructions on where to acquire more coal or food

as well as thinly veiled attempts by British Admiral King-Hall to gather

intelligence on him and his ship. He struggled to learn where all potential

enemy ships were, and recognized that he was surrounded by enemies.

|

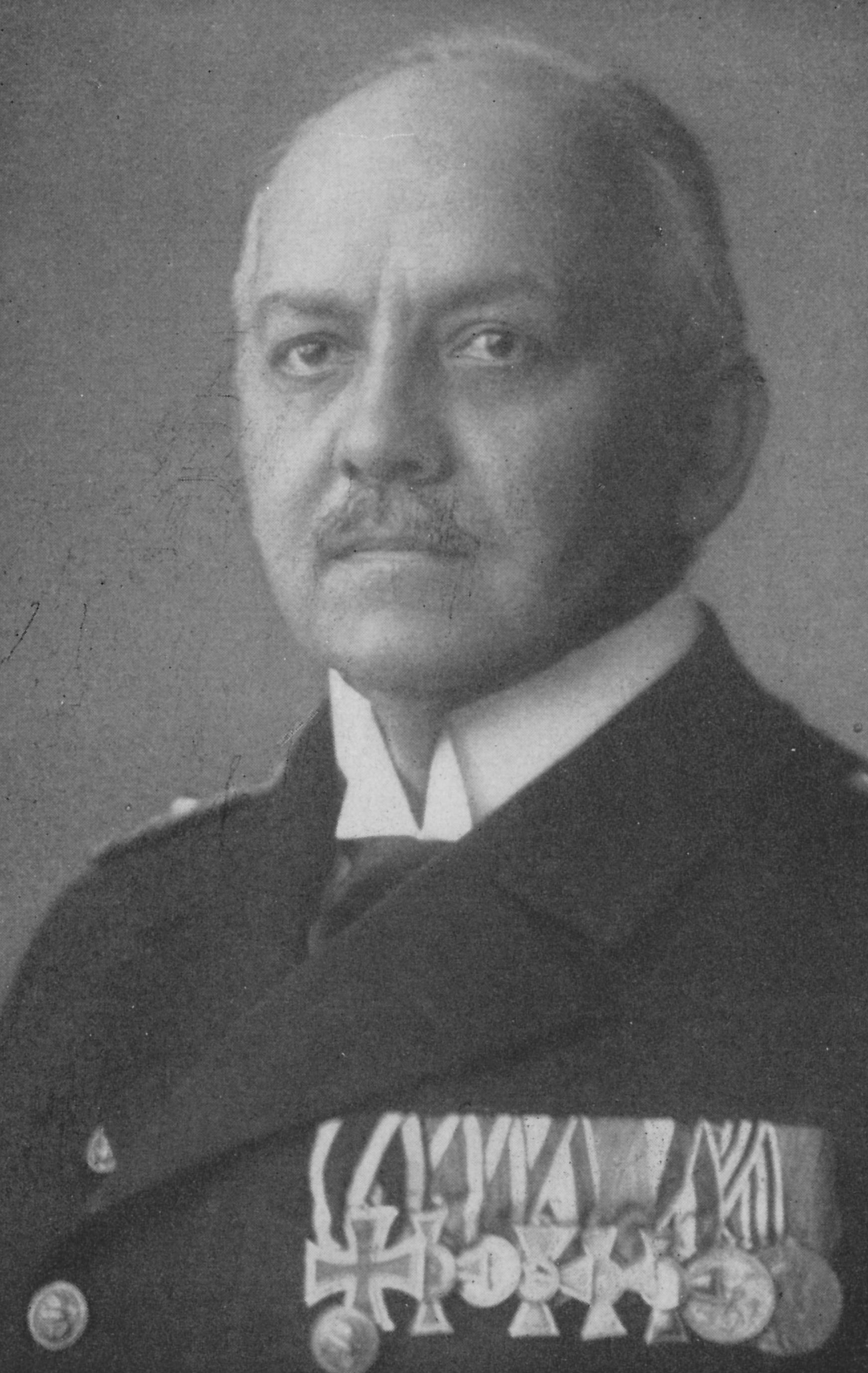

| Maximilien Looff, commander of the Konigsberg. He would receive praise for his dogged performance, but would also spend much of the war butting heads with Lettow-Vorbeck. |

These

enemies consisted mostly of British ships, with a couple French ships around

Madagascar. Admiral King-Hall hoped to intercept German merchant ships to

prevent the possibility of their conversion into armed merchant cruisers. He

decided that the island of Zanzibar, positioned off of German East Africa,

would serve as the ideal central base for any future naval operations. The Konigsberg was outnumbered, but was more

up-to-date than most of the British ships. Looff hoped that his ship and his

crew would outperform the enemy and make up the numbers game. His first major

action predated the start of the war, when in late July three British ships

tried to trap him inside Dar es Salaam’s harbor. His crew outran them and

escaped to the open seas.

With

war verified, the Konigsberg set out for

German East Africa. Loof radioed all German merchant ships to get to the safety

of ports in German East Africa as he guided his ship south. The main concern

was the coal supply. With all nearby ports and fueling stations under hostile

or neutral control, the Konigsberg

needed to borrow from other German ships or raid for fuel supplies. If it did

not get coal, it would not reach German territory. The Konigsberg gave chase to the first non-German merchant ship it saw,

only to learn that it had expended precious coal to run down an German merchant

ship. The two ships had both mistaken each other for the British and acted

accordingly. Looff replenished his coal by taking some from every German ship

he encountered. The Konigsberg’s

hunger for coal was still not satisfied when it effortlessly captured the

British City of Winchester. The coal

aboard the British steamer was of inferior quality and one of Looff’s

subordinates argued that it would be safer to not use it at all. Bombs were

planted and detonated on the City of

Winchester, sinking it. Having just made its first kill, the Konigsberg high-tailed it east to escape

Rear Admiral Pierce’s East India Squadron. Its coal reserves were finally saved

by a rendezvous with the steamer Somali.

The two ships had spent the last several weeks playing cat-and-mouse with the

British until they could finally meet, and in the nick of time. The Somali bore

coal which gave the Konigsberg the life it needed to get to the defense of

German East Africa.

But

the Konigsberg’s woes were not over

by a long shot. The British had already bombarded Dar es Salaam, destroyed some

of its facilities, and gotten Schnee’s pledge of neutrality. The original

destination of the Konigsberg was no

longer safe. Needing time and space to fix up his ship, Looff decided to head

for the Rufiji Delta. This was a wise move. The Germans were the only Europeans to

have thoroughly studied and charted the Rufiji’s tangle of waterways. He could

thus easily elude the British Navy should it try to follow him into the delta.

While refueling and refitting inside the delta, Looff learned that a British

ship, the HMS Pegasus, was undergoing

repairs in the port at Zanzibar. The Pegasus

had earlier tried to force the German port of Bagamoyo to accept neutrality.

When the port had refused the Pegasus

fired on its customs house. Now it was in port for engine repairs.

The

Konigsberg emerged from the delta and

steamed for Zanzibar. On September 20 it surprised the Pegasus and within twenty minutes had turned it into a cauldron of

smoke and fire. The Pegasus, under

Captain John Ingles, put up a valiant effort, but its fire waned as its guns

were taken out. The Konigsberg’s

Radio Officer Niemeyer was able to jam enemy communications, ensuring that no

aid came, save for a tugboat, the Helmuth,

which was unfortunate enough to appear during the battle. It was quickly sunk.

The victorious Konigsberg departed,

dropping barrels overboard to give the illusion of mine-laying and deter any

pursuit. The Pegasus clung to life,

it engines still functional enough for it to move. Its crew tried to get it to

shallow water and beach it for repairs, but could not make it in time. At 1430

hours, the cruiser capsized and sank. British casualties numbered 39 killed and

55 wounded to none for the Germans.

By

the end of September 1914, both Lettow-Vorbeck and Looff had shown defiance in

the face of overwhelming odds, but their trials had just begun.

Next Month: The Sting of Defeat! Britain launches a major

offensive on German East Africa. Little do they suspect how formidable the

Schutztruppe, as well as the native environment, can be.

Sources

Citino, Robert. The Path to

Blitzkrieg: Doctrine and Training in the German Army, 1920–1939. Stackpole Books, 2008.

Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. New York: Harper Collins, 2012.

Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. New York: Harper Collins, 2012.

Farwell, Byron. The

Great War in Africa, 1914-1918. New York: Norton, 1986.

Gaudi, Robert. African

Kaiser: General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918.

New York: Caliber, 2017.

Hoyt, Edwin Palmer. The Germans Who Never Lost. W.H. Allen & Co., 1977.

Hoyt, Edwin Palmer. The Germans Who Never Lost. W.H. Allen & Co., 1977.

- Guerrilla:

Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck and Germany’s East African Empire. New

York: Macmillan, 1981.

Louis, Roger. Great Britain and Germany’s Lost Colonies: 1914-1919. Oxford University

Press, 1967.

Miller, Charles. Battle

for the Bundu: The First World War in Africa. Macmillan Publishing Co.,

1974.

Naval

Staff Monographs (Historical) Vol. II. Monograph 10.-East Africa to July 1915.

Monograph 5. Cameroons, 1914. Naval Staff, Training

and Staff Duties Division, January 1921.

Paice, Edward. Tip

& Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa. Phoenix, 2008.

Reigel, Corey W. The

Last Great Safari: East Africa in World War I. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman

& Littlefield, 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment