The Lesson of

Jassini

Lettow-Vorbeck

prepared for his offensive against Jassini. Early in January, Lettow-Vorbeck

scouted ahead with one of his captains. He created as accurate sketch as

possible of the terrain and enemy dispositions. The most notable feature of

Jassini was its large coconut plantation. The fort at Jassini itself was only

manned by a small advance force, with the bulk of the British force miles to

the north (now under the command of General Richard Wapshare). In Jassini’s

rear was a small river, the Sigi. The commander of Jassini’s garrison was an

Indian Colonel, Raghbir Singh. Under him were Indians and elements of the KAR.

If Lettow-Vorbeck hit it swiftly enough, he could overwhelm the small garrison

and remove the northern threat to Tanga. He hastened back to his army and

brought it up. He was careful and secretive in organizing his men, hoping for

the element of surprise. Contingents went ahead, going north around the town to

straddle the roads north. They hoped to block and delay any relief efforts for

the garrison.

The

battle began on January 18. The surprise attack was looking to be a success,

but internal dissensions prevented it. Among the Askaris were Arabs, and they

were very angry with their commander. Lettow-Vorbeck wanted few impediments to

his force’s mobility, and had ordered the Arabs to leave their boys behind.

These young males helped the Askaris carry their gear, and performed certain

other services for the Arabs. Stripped of their youthful companions, the Arabs

waited until they were close to enemy lines and then fired their guns into the

air, alerting Singh’s Indians. They ran to the rear, satisfied that they had

gained their revenge. However, the African Askaris were furious and turned their guns on the Arabs, mowing them down. Having dealt with this treachery, the Schutztruppe

now found itself embroiled in a furious battle.

The

first assaults on the fort did not go well. The Askaris suffered considerable

casualties. Yet, using the brush as cover, the Askaris were able to get in

close on all sides, and Singh was compelled to attempt a retreat. To the north,

a relief column was delayed and prevented from relieving the Indians. As the

tide turned, the center of the fighting shifted to the Sigi River, which the

Commonwealth force needed to cross in order to escape. Fire was exchanged over

the water, many bullets hitting it. In this dangerous environment a Ugandan

sergeant of the KAR, Juma Gubanda, swam across and back in a reconnaissance.

Lettow-Vorbeck’s own orderly, Lance Corporal Ombasha Rayabu, repeated this feat

for the German side, but on one of his forays was killed. Singh’s force was

pushed back on all sides, being confined to the fort (one Indian unit had to

charge through Schutztruppe lines to reach the defenses). The garrison put up a

good fight, refusing to give in as their protective dirt walls absorbed the

impact of shells and bullets. Singh was killed, with British Captain Hanson

taking charge. But they could not fight the midday heat and their thirst. The

effects of heat were so great that some of Lettow-Vorbeck’s men fought over the

liquid contents of a cocoanut. The Entente garrison finally raised the white

flag, out of ammunition and close to dying of thirst.

The

Battle of Jassini is not as well known as Tanga, but it was important for both

sides. On the British side Lord Kitchener Secretary of State for War, was

already skeptical of engaging in colonial side wars. Hearing of another

considerable defeat, he criticized General Wapshare for sending expeditions

without proper intelligence. He ordered him to put Commonwealth forces in a defensive

posture, handing the initiative over to Lettow-Vorbeck. The Schutztruppe

suffered 86 killed and around 200 wounded. The British suffered around 200

killed, and up to about 400 captured (many wounded). In terms of hard

casualties the two sides were not too far apart. Lettow-Vorbeck realized the

toll this battle had taken on his force. Between this and the Battle of Tanga

he had lost dozens of good officers.

“Although

the attack carried out at Jassini with nine companies had been completely

successful, it showed that such heavy losses as we also had suffered could only

be borne in exceptional cases. We had to economize our forces in order to last

out a long war. Of the regular officers, Major Kepler, Lieuts. Spalding and

Gerlich, Second-Lieuts. Kaufmann and Erdmann were killed; Captain von

Hammerstein had died of his wound. The loss of these professional

soldiers—about one seventh of the regular officers present—could not be

replaced.”

Furthermore, the Schutztruppe did not have enough

ammunition for more battles of this magnitude. It was time for Lettow-Vorbeck

to fully embrace his vision of a hit-and-run bush war. He resolved to keep his

men mobile, and to hit the enemy with concentrated blasts of force. The first

target of this strategy would be the Usambara Railway.

Rail War

|

| A train stopped at a station on the Usambara Railway. |

The

Usambara Railway had been constructed to connect Tanga to other parts of German

East Africa as well as British East Africa. The specific stretch that

Lettow-Vorbeck targeted was a 100-mile portion straddling the colonial border.

The Schutztruppe was to avoid any major battles. Instead it would send out

small patrols to destroy rail tracks, assail trains, and hit small British

outposts. With the use of captured horses and mules, the Schutztruppe was able

to double its mounted force. However, most of the patrols would have to go it

on foot through the wilderness.

The

ensuing campaign is colorful to western readers, full of exotic dangers. The

terrain between the Schutztruppe’s base of operations and the targets was

virtually a desert, with sustenance provided by oases and animals passing

through. Lettow-Vorbeck recalled one mounted patrol that lost its horses after

dismounting to defeat an Indian force. Trekking back, they would have died of

thirst and hunger if they did not first come upon a Maasai cattle corral with

milk and then found and killed an entire elephant, sharing its meat. The

combination of heat and thirst killed several men, and forced others to drink

their own urine or in rare cases the blood of birds. Hunting was difficult, as

shooting was forbidden. The sound of a rifle aimed at a wild beast could carry

far in this environment, and tip off the British. Despite these difficulties,

the Schutztruppe was generally successful, aggravating British command to no

end.

| A German officer leads mounted Askaris. Notice that many of them are riding mules. They used whatever mounts they could (in German South-West Africa many employed camels). |

The

British counter-response was of mixed success. Its overall command was lacking.

Richard Wapshare, who had contributed to the British disaster at Tanga, was

hastily put into Aitken’s role after that particular battle, only to be demoted

in March of 1915 and sent to the Mesopotamian front. After him came

Brigadier-General Michael J. Tighe, who was even more unqualified to deal with

the assaults on the railway. He suffered consistently from gout and dealt with

it through alcohol, hampering his response to the constant raids. As at Tanga,

many of the Indian troops in this area were of second-rate quality. In one

infamous incident which may be apocryphal, one group spent all night awake and

armed They had heard something in the darkness and nervously looking about in

every direction. Fearing a German encirclement, they were embarrassed to learn

that they were in fact surrounded by baboons. The most qualified soldiers, the

native King’s African Rifles, were sidelined when one influential officer

decided that they would be no use, despite the fact that Lettow-Vorbeck was

experiencing great success with his own native black troops. Popular history writer

Edwin Hoyt summarized the dire coordination of the Commonwealth force: “Von

Lettow could not have been luckier than to have against him so disorganized a

British political and military machine.”

However,

there were bright spots. Richard Meinertzhagen took a personal hand leading KAR

counter-patrols. In addition to scoring a few victories, he came up with the

idea of installing signs by watering holes. These signs warned of contaminated

water. He further fleshed out the illusion by placing dead birds around them. For

a while the Askaris and their German officers took them seriously, or were at

least unsure as to whether they spoke the truth of lies. This exacerbated the

water situation for many Schutztruppe patrols. Meinertzhagen also ran an

intelligence service, able to predict many German movements. These movements

were often deduced by agents who recovered scraps of paper from

Schutztruppe-used latrines.

The

patrols often consisted of groups numbering less than ten men. This enabled the

wildlife to take a more active role. Occasionally a rhino, irate at these

intrusive humans with their loud firing sticks, would charge into the fray. It

would claim victory as both sides fled. Sometimes soldiers would find themselves

confronting lions at watering holes. If Meinertzhagen is to be believed, he was

once aided by the local fauna in a victory. He noticed a group of herbivores looking

warily in one direction. Following their gaze, he crawled over a ridge and

espied a German patrol. He got a rifle and started picking his foes off. One

German patrol under Afrikaner Lieutenant Pieter Krueler lost half its men, but

not from the British. They found one of their men dead, evidently killed by a

lion. They then spent a night surrounded and sometimes attacked by a pride of

lions. They had to assemble in a circle, uncomfortably crouching while firing

at any feline intruders. The sun rose to reveal two dead lionesses, but also

some dead men.

|

| A rhino and her calf. Such a pair was once mistaken for German cavalry by excited Indians. |

One

of the larger actions of this time was the Battle of Bukoba, form June 21 to

23, 1915. Bukoba was a wireless radio station off of Lake Victoria, in

northwestern German East Africa. A fleet of British steamers headed by General

Stewart brought 1,500 men against the 200-man garrison. Included in this force

were the Frontiersmen. Led by Colonel Patrick Driscoll, the Frontiersmen

consisted mostly of big game hunters, among them the 64-year old Peter Selous.

It was an eclectic group that included the likes of Siberian convicts, former

circus clowns, deserters from the French Foreign Legion, a millionaire, and even

William N. Macmillan, a former hunting pal of President Theodore Roosevelt. At

first he Bukoba expedition looked like it might be another British disaster.

The fleet landed in a swamp, where the men had to slog their way through German

fire. By the 23rd they had managed to break through, scattering the

much smaller opposing force and taking the town at the cost of about 150 killed

and wounded. Bukoba was a much-needed success. Meinertzhagen, who had come

along, demolished the radio station, seriously harming the Schutztruppe’s

communication. But the undisciplined Frontiersmen went on a looting spree,

tarnishing the first prestigious British victory in the area. Beyond stealing

civilian property, they burned down many of the buildings and raped many of the

women. Reluctant to admit what had happened under their command, Stewart and

the other officers reassigned the Frontiersmen to guarding the railway, where

their numbers would be devastated by high casualties.

Bukoba

and several small actions aside, the Germans enjoyed massive success, in no

small part due to British negligence. They repeatedly captured and looted

outposts, destroyed bridges, and derailed trains. At least twenty trains were

derailed, completely disrupting the timing of British East Africa’s supply

line. Eventually somebody came up with the idea of attaching two empty cars to

the front of the train. These served as minesweepers, taking the blast and

saving the main engine. Throughout 1915 the Schutztruppe kept the British

colonial forces on their toes. Lord Kitchener believed in holding the course, that

a defensive posture was best, that it would be a waste of men and resources to

go for a conquest of German East Africa. However, many in the war office were

determined to solidify claims over German colonial territory, and searched

about for a commander to lead a great invasion.

The End of a

Good Run

As

Lettow-Vorbeck’s star rose, the SMS

Konigsberg under Captain Maximilien Loof put up its own defiant fight. The

British fleet tasked with chasing it down expanded, but it had trouble finding

the ship, which sat camouflaged in the winding Rufiji Delta. The waters were

too shallow for the fleet’s larger ships to get close enough for a bombardment.

They did attempt to sink a ship to block the way out to sea. Though successful

in this blocking action, they did not account for the maze of alternate

waterways that the Konigsberg could

employ.

The

Konigsberg was always short on

supplies. From sea it hoped for the infiltration of blockade runners, posing as

British or neutral Danish ships. One such attempt from the Kronborg, posing as a neutral Danish ship, was thwarted when British

naval intelligence broke the Konigsberg’s

codes and thus intercepted the blockade runner. Also tricky was repairs. There

was no suitable facility nearby and no modern method of overland transport. To

repair one of the Konigsberg’s

boilers, a thousand Africans were required to haul it on foot all the way to

Dar es Salaam. In about a month the boiler was repaired and hauled back,

as good as if it had been worked on in Germany itself. For all its dogged

resistance, the ship’s crew experienced a plummet in morale. They were cooped

up in the delta, with no safe way to break out and make it back to Germany.

Worse, they were heavily afflicted by malaria. Many were at least able to escape

the ship itself when, to Captain Loof’s annoyance, Lettow-Vorbeck seized half the

crew to bolster his Schutztruppe.

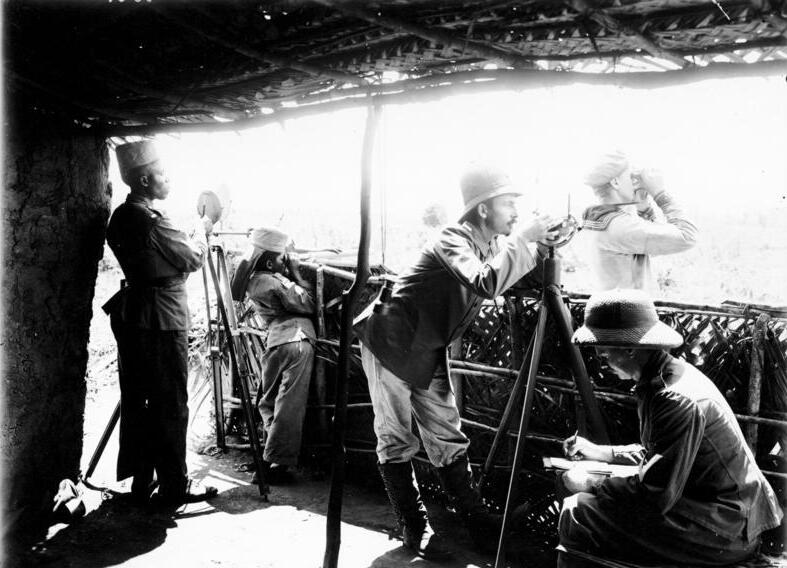

|

| An artillery observation post helps direct some of the guns placed in the delta to ward off any British ships looking for the Konigsberg, |

The

British also experienced frustration as it searched for the elusive cruiser. In

addition to hastily improvised minefields, small detachments of German soldiers

inhabited the delta land. A small British ship, the Adjutant, went on a scouting mission and found itself bombarded

from land guns on two sides. It quickly surrendered. The Commonwealth also

employed planes to scout and hopefully bomb it. These attempts failed

miserably, the primitive aircraft literally breaking down in the tropical heat.

Then a trio of seaplanes finally spotted the ship, only to be shot down.

Despite

the losses in aircraft, the British Navy finally had a bead on the Konigsberg’s general location. The

problem now was how to get to it. They enlisted the aid of an Afrikaner, Peter

J. Pretorious. Pretorious had spent much time in the delta area hunting large

animals, including elephants. Now he explored it further, putting the various

canals and other waterways down on a map. He also found out the latest location

of the German cruiser. Once he had finished, the British had an attack route,

to be used by shallow-draft monitors. These ships included the Mersey and Severn. As monitors, they were not particularly well-armored, but

wielded large guns that could hopefully take down their target.

|

| Above: The HMS Mersey Below: The HMS Severn |

Guided

by Pretorious’ information and aerial reconnaissance, the monitors were able to

launch an attack on July 6, 1915. They started their assault run under the

cover of darkness. Planes fitted with radios attempted to guide their fire.

Though harried by sea and air, the Konigsberg

frustrated the attack. Accurate shrapnel fire against the planes kept them

flying around in circles, unable to collect their bearings. It also got the

better of the naval duel. It took out a gun on the Mersey along with four crewmen, set fires on the deck, and

destroyed an accompanying small boat. The Mersey

withdrew and the Severn took over.

Its crew fared much better, scoring four hits on the Konigsberg that knocked out a gun and even wounded Captain Loof.

However it too had to steam off under the pressure of German guns.

On

July 11 the monitors went for a second try. The strategy was more particular

this time. The Mersey was to draw

German fire while the Severn went for

the kill. This did not pan out, as Loof was determined to hit both ships

simultaneously. At this point, however, the Konigsberg

was seriously short on ammunition. Only half of its guns could duel with the

British. Believing they had curtailed the German firepower themselves, the

Commonwealth seamen felt emboldened. Their effectiveness was much greater this

round. One shell penetrated the lower decks of the Konigsberg, causing fire that threatened to hit the ammunition

magazine. Loof was forced to flood and thus lose his reserve ammunition to

prevent an explosion. Then another shell hit the cabin, wounding him all over

and leading his crew to believe he was dead. He was still alive and able to

tell his men to start abandoning ship. The great German cruiser could not

survive much longer. Loof destroyed any guns that could not be carried by his

surviving crew (they had lost over fifty in killed and wounded) and then

detonated two torpedoes in the hull to sink the ship down to its masts.

|

| The wrecked SMS Konigsberg. |

The

Konigsberg’s defiant run and the

largest threat to the British Empire’s Indian Ocean trade had ended. But the

war was not over for its crew. Some of the surviving guns were put into coastal

emplacements. The rest were reassigned as field artillery. They followed Loof

and his men into the Schutztruppe. Lettow-Vorbeck would need all the help he could

get. Pretorius, the game hunter who had helped sink the Konigsberg, was just one of many South Africans coming north to

conquer the last Germany colony.

Next:

African Apocalypse! We take a look at the African perspective of the East

African campaign. Some eagerly pitch in with the colonists in hopes of

advancement. Others see a chance for liberation. The cost for Africans,

including millions who have no interest in the war, will prove to very high.

Sources

Farwell, Byron. The

Great War in Africa, 1914-1918. New York: Norton, 1986.

Dane, Edmund. British

Campaigns in Africa and the Pacific, 1914-1918. London: Hodder and

Stoughton, 1919.

Gaudi, Robert. African

Kaiser: General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918.

New York: Caliber, 2017.

Heaton, Colin D., and Lewis, Anne-Marie. Four-War Boer: The Century and Life of Pieter Arnoldus Krueler.

Havertown: Casemate Publishers (Ignition), 2014.

Hoyt,

Edwin Palmer. The Germans Who Never Lost.

W.H. Allen & Co., 1977.

-

Guerilla: Colonel

von Lettow-Vorbeck and Germany’s East African Empire. New York:

Macmillan, 1981. Louis, Roger. Great Britain and Germany’s Lost Colonies:

1914-1919. Oxford University Press, 1967.

Lord, John. Duty,

Honor, Empire: The Life and Times of Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen. New York:

Random House. 1970.

Miller, Charles. Battle

for the Bundu: The First World War in Africa. Macmillan Publishing Co.,

1974.

Paice, Edward. Tip

& Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa. Phoenix, 2008.

Reigel, Corey W. The

Last Great Safari: East Africa in World War I. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman

& Littlefield, 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment