The Fight of September 13

The Missouri State Guard was in sight of Lexington. Price wasted little time in attempting to seize the town. He deployed his infantry and artillery and gunned for a bridge which would quickly take his force into the town. When the Rebels crossed the bridge, Mulligan sent out two companies of the 13th Missouri as well as company K of the 23rd Illinois. The two sides confronted each other within the cornfields of farmer Isaac Hockaday, the Federals behind hemp bales and the State Guardsmen behind a fence. Hockaday had gone out to look for his neighbor so they could organize an evacuation. Instead he found himself cut off from his family as his corn field turned into a fire zone. Later reflecting on the chaos around his and his neighbors’ homes, and the ensuing destruction to their property, he wrote sadly, “I feel as if we had better lost all of our negroes than suffered as we have already…” Price withdrew from the indecisive skirmish. The Federals took advantage of this break in action to burn the bridge. With more of his army pulling up, Price changed the direction of his attack. He wheeled his army to come from the west on Independence Road.[1]

Price’s new avenue of attack scattered some cavalry pickets. Six companies of Federal infantry exited the town to meet the Guardsmen, hiding in hedges and cornfields on the east side of the road. At the head of Price’s force were horse soldiers. The Federals held their fire until they were just about 150 yards away. Then they revealed themselves. The sudden deluge of fire frightened the horses and the cavalry had to spur away. This gave the infantry problems. The horses ran over a couple unfortunates and others had to run to get out of the way. This also meant they went into battle with a distinct air of confusion, not helped by the well-concealed Federals in the cornfield. After getting behind the infantry, the cavalrymen got off their unreliable mounts and returned to the front to fight it out on foot.[2]

The

tide turned when Bledsoe and Guibor’s batteries unlimbered and hit the east

side of the road with shells. This convinced the Union soldiers to get up and

retreat before the vast hordes of whooping Missourians could cut them off from

the entrenched college grounds. Former judge James McBride led his division across

Independence Road and then an orchard to get into a cemetery. A couple writers

poetically described a scene of the freshly killed lying over the long dead,

but in actuality the soldiers quickly rushed through it without any serious

bleeding. As he reorganized his men, McBride sent his aide and one of Colonel

Edmund Wingo to go atop a rise in the ground for reconnaissance. The elevated

colonel was shot, the bullet ripping through his shoulder with enough force to

knock him off his horse. He was not killed and remounted, riding back to safety

with the other officer.[3]

This

prolonged running fight kept the State Guard

back so that the rest of the Federals could finish their defenses with

“breastworks 3 or 4 feet high”. After more pushing from McBride, the

Federals finally gave way. With great disdain, McBride reported that they “fled

like rats” until they reached the safety of their earthworks. The 23rd

Illinois mistakenly fired on the retreating 13th Missouri, though

thankfully the only damage inflicted was one man wounded.[4]

Little

skirmishes broke out along the entrenchments, but the only moment of note came

when one Guardsman got close enough to plant a flag in the enemy line. He did

not have the backing to cement his claim. The artillery took over around 3:00

PM. One shot almost hit a group of mounted officers outside the earthworks.

They ran inside, claiming that it was their horses, not them, who panicked. This kicked off a ninety minute duel that concluded at

dusk. One officer reported the “satisfaction by a lucky shot, of

knocking over the enemy's big gun, exploding a powder caisson, and otherwise

doing much damage.” The artillery fire did not produce much in the way of

casualties, most of those horses. One ball passed through three mules and

continued with barely abated speed. The shooting of the big guns may not have

drawn much in human blood, but it did create panic among the mostly green men

in the entrenchments. Many ran for what they considered safer trenches. Others

wildly fired their weapons. Disgustedly, Mulligan said “those who were not

shooing at the moon were shooting above it, into the earth, or elsewhere at

random”. This was dangerous because ammunition needed to be conserved for an

impending siege.[5]

The

State Guard commanders were satisfied that the enemy was “speedily driven from

every position.” The fight on Independence Road went through much terrain:

road, cornfields, orchard, cemetery, the streets, and finally the trenches. The

participants were thus greatly surprised when they learned the low tally. The

State Guard suffered 2 killed and less than 10 wounded, the Federals 1 killed

and six wounded.[6]

Digging In

Mulligan’s

subordinate officers insisted that they evacuate, either using two available steamers

to cross the Missouri River or marching by foot to Sedalia. Mulligan opted to

stay. He wanted to win this battle and was confident that reinforcements would

come. Besides, both escape plans were open to attack. They might as well fight

from the safety of their earthworks. Price also resisted the suggestions of his

officers. They wanted to press the attack, but he decided it would result in a senseless,

bloody failure, as they had barely any ammunition until the wagons from Osceola

arrived. Perhaps if Mulligan knew how desperate his enemy’s supply situation

was, he would have attempted an evacuation.[7]

Both

sides settled in for a small scale siege. A “drenching rain” soaked the

battlefield on September 14. Though fighting was postponed, the Unionists

continued to work on their earthworks, standing “knee deep in mud and water” as

they shoveled up earth and packed it in piles. Indoors, the basement of the

Masonic college was given over to making cartridges while at the foundry

ammunition was made for the cannon and mortars.[8]

Between the main entrenchments and the protective ditch were “confusion pits,” placed

so as to make the enemy stumble. There were also mines. These were not the

technological terrors that were favored by the Confederates on the Virginia

Peninsula and at Charleston Harbor. They were simply fuses running through

metal pipes (ripped straight out of the Masonic College), attached to buried

gunpowder. One engineer suggested that they build wells and cisterns to provide

more water. Mulligan said it was not necessary since they were connected to the

Missouri River. It was a decent argument, but the troops would end up paying

for it.[9]

Mulligan

sent the steamer Sunshine to

Jefferson City, in the hopes that it would bring back reinforcements. It would,

but unfortunately not his. Harris’ State Guard division, moving south to

finally join Price, came across the boat and captured it. Now he used it to

ferry his own troops to Lexington. The Sunshine

itself only spent a short time in rebel captivity. When it passed by the town

of Cambridge Federals fired at it and the new masters abandoned it. Harris’

division also blocked another steamer, Sioux

City, from delivering reinforcements to Mulligan.[10]

Fremont

was indeed looking about for reinforcements. Just the previous month he had

failed to send any support to Lyon, resulting in that general’s desperate

defeat and death at Wilson’s Creek. Many in the Federal government and army now

castigated Fremont for his dilatoriness. His efforts on behalf of Mulligan at

Lexington were more energetic, but would prove to be almost as ineffectual. On

September 13 Fremont wrote to Colonel Jefferson C. Davis, “I send you today two

regiments, to remain at Jefferson City. In the mean time send forward

immediately two regiments to the relief of Lexington, provided nothing has

occurred since your last dispatch to render it inexpedient…Move promptly.”[11]

Davis

could directly reinforce Mulligan, but he also wanted to stop another State

Guard force under Martin Green before it could in turn bolster Price’s

besiegers. He sent 5 companies of the 22nd Indiana with some

artillery on the War Eagle to intercept

Green. The other half of the 22nd would march by land to Booneville.

When Green had already crossed the Missouri River, he recommended to Fremont

that he send Sturgis to Lexington while Davis would send some of his men to

pursue and hit Green from behind.[12]

Sturgis, who had commanded the Federal retreat from Wilson’s Creek the previous

month, left Macon on the 16th with a regiment of Ohioans. They used

a train and then disembarked 40 miles north of Lexington, heading there on

foot. Brigadier-General John Pope sent more men to intercept some of the

numerous rebel elements flocking towards Lexington. Fremont ordered Davis to

disperse a rebel force in Pettis County and then head for Lexington, but Davis was

slow to move, claiming to need more men and supplies for this kind of mission.[13]

With the constant delays and halts by Davis, Fremont sent an additional order

to James Lane in Kansas to provide relief for Mulligan. Recognizing that the

Kansans worked better as mounted raiders, he ordered, “You will harass the

enemy as much as possible by sudden attacks upon his flank and rear.”[14]

Back

in Lexington Price plotted his next move. The Confederates solidified their

positions as Harris and others arrived with their men. Rains, with the largest

division at 3,052 men and six guns, held the north and northeastern section,

down to Main Street. Parsons’’ division lay along Main Street. Slack’s was on

his left, touching the river. Upon his arrival Harris formed along the river,

completing the circle. Steen and part of Clark’s division were held in reserve.

Price placed McBride in support of Harris, as well as a couple artillery

batteries. Bledsoe’s battery took a northeastern position while Guibor’s was

distributed across the MSG-occupied areas of the town.[15]

He refused to launch a direct assault until he was sure it had a good chance of succeeding. He said “It is unnecessary to kill off the boys here. Patience will give us what we want.” He hoped to avoid violence altogether. He sent a messenger under a white flag to the fortifying Federals. Through him, he gave Lexington’s defenders a chance to evacuate the city as paroled prisoners. Mulligan scoffed at the offer and claimed that in a few days his men would drive them back to southern Missouri.[16] He was likely anticipating a convergence of reinforcements from around the state. However, these would-be saviors were encountering problems of their own.

Battle of Blue Mills Landing

Sturgis’ column would have to cross the Missouri River. The State

Guard had already beaten him there. In order to push through the Federal guards

at the fords and reach Lexington, the Rebels gathered as much men together as

possible at St. Joseph. They formed an impressive 3,500 man force. This

included 5 regiments of infantry and 1 of cavalry from the 5th

Division, the same from the 4th Division, and Captain E.V. Kelly’s

battery of three guns (on nine-pounder and two six-pounders). Price sent David

R. Atchison, a long-time member of the Missouri State Militia, to guide the recruits

to Lexington.

He directed them to Blue Mills Landing. The crossing of the Missouri River took

a long time, especially with the 100 wagons the rebels had with them. The

crossing began on the 16th. The next day many of them had not yet

passed over the water.[17]

The approaching Federal opposition was divided between two

separated commands. Colonel Robert F. Smith and the 16th Illinois,

along with part of the 39th Ohio, was stationed at the St. Joe

railroad bridge on the Platte River. Lieutenant Colonel John Scott was

currently at Cameron with his 3rd Iowa and four companies of

Missouri Home Guards. Sturgis was to command these men and he sent messages in

an effort to coordinate and unite them. Colonel Scott’s force was to join

Colonel Smith’s at Liberty. From there they were to drive the State Guard from

St. Joseph. Then they would be able to cross the Missouri and come to the

rescue of Mulligan.[18]

Scott

impressed several civilian wagon teams to carry his men’s supplies. A Captain

Schwartz sent a gun with a team of 14 fellow German artillerists to give Scott

more firepower. The Federals marched through rainy weather. The roads grew a

little slippery, but not muddy enough to seriously impede their marching. They

made it only seven miles on the 15th, but made up for it on the 16th.

On September 17 Scott was wondering where Smith was (Sturgis’ message informing

their next movements had failed to reach him). He could now hear shots from the

other side of the river, likely from sniping and artillery fire at Lexington’s

earthworks. He felt he had to do something and set out with his men. For once

local intelligence provided accurate numbers of the enemy, claiming that there

were at least 3,000 guardsmen in the area.[19]

The

State Guards on the north side of the Missouri River got wind of the

approaching Federals and set up an ambush. Mounted men from the Unionist

Caldwell Home Guards drove in the Rebel pickets. They rode into an ambush from Colonel

Richard Chiles’ dismounted cavalry. The Home Guards were armed with muskets,

difficult to fire from horseback, and got the worse of the exchange, with 4

killed and 1 wounded. Chiles withdrew and Scott pressed his men further along

into dense terrain. One of the Iowan soldiers remembered, “We were in a wooded

bottom which continued to the river, interrupted by one or two small

corn-fields. The timber was very dense, and the fallen trees and tangled vines

rendered it almost impenetrable.” Scott had to keep his men to the road, with

skirmishers scouring the brush to detect the Rebels.[20]

The

officers of the State Guard indeed realized the great potential of this

environment, which was “an almost impenetrable jungle.” Years earlier a tornado

had uprooted many of the trees, which now served as great places to position

riflemen. There was also a slough alongside the road which could serve as an

embankment. Colonel Jeff Patton placed his men, numbering about 700, on both

sides of the road. The Federals moved forward, nearly blind. Scott led his men

very close to the enemy, unaware of their precise location. “All at once, we

heard a few sharp reports, and then a deafening crash of musketry.” Patton’s Guardsmen,

heavily outnumbering Scott, produced a thick and deadly hail of fire. “The

situation was disastrous in the extreme. It did not require a second thought to

comprehend it. While marching to attack the enemy, he had ambushed us and

attacked us in column.” The men fanned out in disorganized fashion, quick to

get off the dangerous road and into the cover of the brush.[21]

The

German artillerists around Scott’s sole gun found themselves exposed and in

shooting distance of the enemy’s short range shotguns and hunting rifles. While

the crew tried to load the gun for another shot, the man with the primer was

shot dead a few feet in front. The Federals wanted to fire back, but “saw

nothing to shoot at.” They still fired fast and furiously, if blindly, into the

brush. This at first rattled Patton’s green Guardsmen. However they soon

steeled themselves and let loose effective volleys. The situation for Scott’s

men grew increasingly dire. Most of the higher-ranking officers had been shot.

The gun was inoperable under heavy fire. Patton’s Guardsmen was now in a

“crescent,” simultaneously pouring fire into Scott’s front and flanks. A brave

sergeant, Abernathy, led a team of Iowans to the gun and managed to remove it.

In all the gun only fired twice in the entire fight as it was too exposed to

man in a hail of lead. The Federal column started to disintegrate and go

backwards.[22]

The

Federals ran into a wheat field where the shooting continued. The Federals fled

some more, leaving their ammunition wagon stuck between two trees. The State

Guard chased the federals “like hounds on a wolf chase.” All attempts to stop

and form a defensive line fell apart. The skirmish of Blue Mills Landing (or

the Battle of Liberty) was the latest rebel victory. Casualty estimates for the

State Guard are not clear. One source puts it at a couple killed and 20

wounded, while the National Park Service puts it much higher at 70. Estimates

for the Federals are also varied. The high estimate is 20 killed and 60 wounded

and the lower 56 killed and wounded. Though he was soundly beaten, Scott still

linked up with Smith. Smith’s men were weary from hard marching, and a message

from Pope urging him to press towards Lexington failed to reach him. As a

result, the Federals withdrew further.[23]

The Siege Continues

Churchill Clark

While

defeats and other circumstances stymied Federal reinforcements, the siege of

Lexington continued without any major assault. Mulligan had his men continually

improve their earthworks, determined to throw back the next large attack should

it occur. This did not mean that men were idle in the art of killing. Both

sides had managed to convert workshops into makeshift ammunition factories.

While the quality of the missiles was poor, these recently molded balls allowed

for continual artillery sparring. One youthful officer who rose to the occasion

was Churchill Clark from Parson’s division. Clark was the son of Meriwether

Lewis Clark, a State Guard general, and thus the grandson of famed explorer William

Clark. He had just started at West Point when the war began. Others expected

him to graduate in 1863, but he dropped out to fight for his home state. Clark

had with him an Indian (from which group not specified) who had decided to

fight alongside the ancestor of the friendly explorer and Indian agent William

Clark. Clark served.[24]

Clark took possession of a blacksmith’s forge to create small fiery six-pound

shot. He planned to burn down the Masonic College, the headquarters of the

Federal forces. Many of the balls missed their mark and most of the others were

tossed back out by the building’s occupants before they could do their work.[25]

While their artillery tried to weaken Federal lines, small groups of impatient

Guardsmen made forays into town. They started sharp and pointless skirmishes

which at best resulted in a few more killed and wounded men.[26]

Those

within the Federal entrenchments also itched for action. David H. Palmer, an

Illinoisan, disguised himself “in an old check shirt blue overalls and an old

straw hat.” Boldly, he went on a spy mission without obtaining any permission

from his superiors. He came upon a quartet of mounted Rebels and one shouted at

him to “Come up here!” Palmer initially felt nervous, but was then overcome by

confidence. The Guardsmen grilled Palmer about the numbers and positioning of

the defenders. Palmer claimed he did not know much, being a recent traveler

from Kentucky. He also claimed to be searching for a widow’s missing cow.

Palmer then asked a series of “idiotic questions.” This convinced the mounted

men that he was a simpleton and they let him go. The Illinoisan walked south

where he briefly met more Rebels. Palmer soon got lost in a dark forest and

grew anxious. He “imagined that a Rebel was behind every tree; that old stumps

were Rebs aiming their guns at me and every moment I expected some devil to

yell Halt!” Using the river, Palmer was able to get back to Federal lines and

report to Mulligan. Despite his violation of military rule, almost tantamount

to desertion, he impressed the colonel with his audacious attempt at intelligence-gathering.[27]

The

soldiers on both sides were getting antsy. Some of the Guardsmen in particular

were aggravated by the lack of action, with the enemy so close. In a diary

entry from September 17, one castigated Price for the delays and accused him of

over-sleeping. “We will attack tomorrow if Gen. Price wakes up in time.”[28]

Price was indeed planning to attack the next day, but still hoped to avoid a bloodbath. He sent two more messages to Mulligan on the 17th. One was another demand that the Federals evacuate Lexington. Once again Mulligan refused, and his men continued to take advantage of Price’s hesitance to attack to further strengthen their entrenchments. The second message was addressed to the civilians, asking them to leave and find safety. Most agreed, “so there went out from the town an army of women and children to take refuge in country houses in numbers sufficient to tax the hospitality of these to the utmost.” They either found safer homes further from the college grounds or went deeper into the countryside. Of course many, including the woman who provided the last quote, refused to leave. They were too tempted to see the battle for themselves, whether out of curiosity or a desire to see their favored side win.[29]

The Big Assault

To

the chagrin of the Missouri State Guard, the Federals were equipped with

long-range rifles so they could take potshots at them, but they could not reach

them with their own weapons. The advance guard pulled back to avoid wasting any

of their precious powder, ammunition, and percussion caps. The remainder of the

Rebel force moved up and the enemy pickets were only able to give them a

“tolerably hot fire” before breaking. Guibor’s battery followed the infantry

and took position on Cedar Street, from where it could blast the enemy’s works.

The men approached the ring of Union defenses “as implacable as fate.” It was

quite a sight for their waiting opponents. “They came as one dark moving mass,

their guns beaming in the sun, their banners waving, and their drums

beating-everywhere, as far as we could see, were men, men, men, approaching

grandly.”[30]

On

the north side of the town Rains’ men also drove in the pickets. Bledsoe and

Churchill Clark’s batteries took positions and began their bombardment of the

earthworks. Rains offered a gold medal to whoever could knock down an enemy

flag at the southeast corner of the Federal circle. Churchill Clark won the

challenge and took extra delight in seeing the Unionists run around the

trenches under his artillery fire. Back on the west side Harris’ division

followed Parsons’ in, imitating their movements as until they shuffled

alongside them. One cannonball came flying at a group of his men. Their

lieutenant ordered a change in formation that ensured that it sailed harmlessly

past. Harris’ artillery set up at an intersection and rained fire on the

Federal trenches. Harris provided a guard for his guns, one of the few

companies in the army that was armed with minie rifles.[31]

Colonel

John T. Hughes of Rives’ division had the goal of seizing the Missouri River.

This way they could seize the steamboats, Mulligan’s most viable option of

escape from Lexington. Perhaps it was not on Price’s mind, but this would also

deprive the Federals of their main water source in a hot fall. Hughes was

successful and the boats were taken back to the main landing. On them were

horses, foodstuffs, and other goods that would supplement the besiegers’ low

supplies.[32]

In

the town, Guardsmen crowded at the corner of one brick house, using it as cover

from which to pour fire on the artillery. In response, a shell hit the corner,

smashing the brick and sending it flying. Several men were killed or wounded by

this blast and it was realized that bunching about in a small space was not

such a good idea. Shells also hit the trees in the orchard, the shards of grape

and canister knocking their fruit to the ground. The Guardsmen were quite

pleased with this, having an excuse to grab the fallen fruit. Though not ripe

yet, the fruit seemed utterly delicious to men who had only “tasted anything

but green corn for thirty-six hours.”[33]

Due

to the dwindling supply of ammunition, some of the Guardsmen resorted to

finding expended shot from the enemy to shoot back. Some artillery began to

fire rock and gravel, which was noted to work just as well at keeping the enemy

at bay. A few of the Federals certainly buckled under the pressure. Illinoisan

soldier George Palmer derisively recounted how Colonel Marshall of the 3rd

Illinois Cavalry earned the disrespect of his men. The officer spent the whole

fight laying “in the deepest trench he could find.” One soldier claimed he was

so fearful that he urinated.[34]

The behavior of the main Rebel leader was far more inspiring:

“During the heaviest part of the combat,

General Price galloped up, covered with dust, his fine face glowing with the

excitement of exercise, and his eye kindling with the fire of battle. Perfectly

self-possessed, he seemed not to heed the storm of grape and canister, and

taking his position in the rear of the battery, directed the handling of the

guns. Many of the officers urged him to retire or dismount, but with prefect

coolness he kept his position. While here, I observed a grape-shot strike his

field glass, breaking it in pieces. Without the slightest apparent emotion, he

continued giving his orders. Remaining about twenty minutes, he retired,

leaving a lasting impression upon his men, who have ever loved him as their

chief, and admired as their ‘beau ideal’ of honor, and chivalry.”[35]

The

most controversial part of the battle unfolded occurred on the western corner

of the Federal lines. The Anderson House, now serving as a hospital, lay just

outside the entrenchments. Mulligan had ordered a white flag raised above it,

trusting that it would be considered hands-off and a haven for the wounded.

General Harris did not think so. “From a personal inspection of the position

occupied by the hospital I became satisfied that it was invaluable to me as a

point of annoyance and mask for my approach to the enemy.” At noon the State

Guard seized the Anderson House and filled it with sharpshooters. From the

windows, doorways, and roof they poured a “deadly drift of lead” upon the

Federals. They drove a team of artillerists from their gun, silencing the

artillery piece.[36]

|

| A view of the front of the Anderson House. |

This breach of chivalry put Mulligan in a difficult position. He could not very well allow a portion of the enemy to pick off his men with impunity and he would not have his men fire back and inadvertently kill their wounded fellows. It would have to be retaken by force. He gave the task to the Home Guards, but they didn’t have the nerve and refused. A company of his own 23rd Illinois was much more willing. Palmer recalled, “They fired directly into our trenches and after killing and wounding a number of our men, Genl Mulligan saw that they must be dislodged. At the double-quick they covered the 80 yards into the hospital, withstanding the fire until they burst through the entrances. “We reached into the building and drove the enemy from the lower floor some of them running toward the river and some running up the stairs. They kept up a fire from the upper story and from the direction of the River so that many were killed and wounded of our party.” The Guardsmen on the first floor did not stay to fight, running out the opposite end.[37]

The

Federals stopped at the stairs. The officers tried to coax their men up, but

were unwilling to get in front themselves. It was expected that whoever led the

ascent would be shot by the Missourians still upstairs. Palmer, the man who had

gone out in disguise to scout out the enemy days earlier, leapt onto the stairs

and told the men, “If you will follow me I will lead you! We must drive them

out!” The men cheered and followed Palmer up the stairs. As it turned out no

State Guardsman was waiting to receive them. They had locked themselves in the

house’s upper rooms. The attackers forced the doors open. Palmer came into a

room with five sharpshooters. Two of them turned their rifles on him, but then

saw the horde of Federals behind Palmer and surrendered.[38]

|

| The stairs at the Anderson House |

By Palmer’s own admission his comrades behaved vengefully. They believed the Missourians had violated the rules of war by using a hospital as a battlezone. Some claimed they used beds, with wounded Federals on them, as barricades, forcing the Federals to take their time to aim while they could fire as quickly as they wanted. The angry men in blue threatened to move on the five prisoners. Palmer was unable to save them and they were shot and bayoneted. “It was a horrible sickening butchery.” Palmer tried to stop them from further killings, insisting that they spare the Rebels while he pushed aside bayonets.[39] One Guardsman found a way to survive. He got on a bed with a wounded Federal and pulled the blanket over part of his body, disguising himself as another injured Unionist. Another surviving Guardsman named W.H. Mansur would have been executed by firing squad if a less temperamental Federal had not rushed him out of the house to safety.[40]

The

fight for the hospital was the most controversial aspect of the siege. Mulligan

accused the Southerners of breaking the rules of warfare when they entered a

designated hospital and converted it into a sharpshooters’ nest. The

Southerners insisted that the Federals were the first to fire from the

hospital, so their seizure and subsequent use was wholly justified. In truth,

the sequence of events in Mulligan’s report was correct, but a footnote in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War

points out that he had “no military right to expect” that such a strategic spot

should be ignored and that he could be equally culpable for having the hospital

put in such a vulnerable and dangerous spot.[41]

The

fighting on September 18 did not end. The MSG was determined to breach the

Union lines and score a decisive victory. Having lost the Anderson House,

Mulligan set up another hospital in a college dormitory, where a former

physician had to take up his trade again with a shortage of tools. Colonel

Mulligan personally led a charge against Kelly’s two guns to retake the

northwest height. His men retook the position, as well as capturing a flag and

the two cannon. These gains, save for the captured flag, were short-lived, as a

counter charge drove them back to their earthworks.[42]

Soon the encircling assault petered out. The State Guard had failed to force

Mulligan’s surrender. However, they had constricted his perimeter and now

possessed both the water cisterns and the riverfront, cutting the defenders off

from fresh water. Those fighting captured many horses, cattle, beef, and other

supplies.[43]

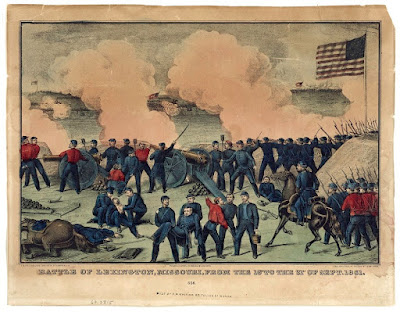

|

| A somewhat exaggerated Harper's Weekly depiction. |

The night of September 18 was a dark one, indeed. Susan McCausland remembered: “The night of this sad day was a lurid one. Hot shell sent from the entrenchments had started fires in three or more quarters, and as night fell these flamed and spread, luridly reddening the sky, and turning a new dread loose upon the town.”[44]

[1] Wood, Kindle,

loc. 531-348; Isaac Hockaday, “Letters from the Battle of Lexington: 1861,” Missouri Historical Review 56, (October

1961), 53-54.

[2] Wood, Kindle, loc. 561.

[3] Wood, Kindle, loc. 578;

Mulligan, 308.

[4] Wood, Kindle, loc. 578.

[5] Wood, Kindle, loc. 595-615;

Mulligan, 308.

[6] OR III, 186; Wood, Kindle, loc.

578.

[7] Wood, Kindle, loc. 649.

[8] Mulligan, 308.

[9] Wood, Kindle, loc. 685-710.

[10] Wood, Kindle, loc. 787.

[11] OR III, 173.

[12] OR III, 173. Randolph V.

Marshall, An Historical sketch of the

Twenty-Second Regiment Indiana Volunteers, (Madison, 1894), 7-8.

[13] Wood, Kindle, loc. 890.

[14] OR III, 181.

[15] History of Lafayette County, Missouri, 346; OR III, 188-189.

[16] McCausland, 134; Wood, Kindle,

loc. 862.

[17] History of Clay and Platte Counties, 208-209; Wood, Kindle, loc.

906; Richard C. Peterson, Sterling

Price’s Lieutenants: A Guide to the Officers and Organization of the Missouri

State Guard, 1861-1865, (Two Trails Publishing, 1995), 15.

[18] History of Clay and Platte Counties, 209; Thompson, 122.

[19] Thompson, 123, 126-127; OR III,

193-194.

[20] Thompson, 128-130; History of Clay and Platte Counties,

209-210/

[21] History of Clay and Platte Counties, 210-211; Thompson, 131-132.

[22] Thompson, 132-133, 141-142;

Wood, Kindle, loc. 921; History of Clay

and Platte Counties, 211; OR III, 194.

[23] History of Clay and Platte Counties, 211; Wood, Kindle, loc.

921-937.

[24] Dr. J.F.

Snyder, Missouri Historical Review,

Vol. VII No. 1 (October, 1912), 4; Michael E. Banasik (ed.), Confederate Tales

of the War in the Trans-Mississippi Part Two: 1862, (Camp Pope Bookshop, 2011), 1-2, 8, 11.

[25] Dr. J.F. Snyder, Missouri Historical Review, Vol. VII

No. 1 (October, 1912), 3-4.

[26] McCausland, 130.

[27] “The Journal of

Major George H. Palmer, Medal of Honor Recipient: A Chronicle of His Early Life

and Participation in the U.S. Civil and Plains Indian Wars.”

http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~luff/genealogy/PalmerGH_Journal.html#lexington accessed June

14, 2021, 4-6.

[28] Wyatt, 10.

[29] Wood, Kindle, 957; McCausland,

131.

[30] Wood, Kindle, loc. 1015. 1051;

McCausland, 135; Mulligan, 309; Anderson, 63.

[31] OR III, 188-193; Wood, Kindle,

loc. 1059.

[32] Wood, Kindle, loc. 1085.

[33] Anderson, 64-65.

[34] Anderson, 65-66; Palmer, 6-7.

[35] Anderson, 66.

[36] OR III, 189-192; Mulligan, 310;

Anderson, 70.

[37] Mulligan, 310-311; Palmer, 7.

[38] Palmer, 7-8.

[39] Palmer, 7-8; Bevier, 56.

[40] McCausland, 133; W.H. Mansur,

“Incident of the Battle of Lexington, Mo.,” Confederate

Veteran 23 (1915), 496

[41] Mulligan, 311.

[42] Wood, Kindle, loc. 1275.

[43] Wyatt, 10-11.

[44] McCausland, 134.

No comments:

Post a Comment