If you have not read the first half, look here.

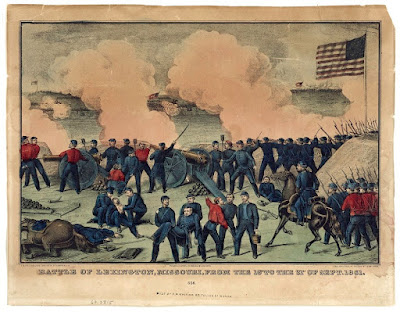

Below are two images from reenactments of the battle. I doubt they recreate the massacre for family audiences.

Final Push

On

the Union left Companies C and I, 1st Kansas Colored, saw about a

hundred men in blue coats pass along their front. They assumed they were from

the 2nd Kansas Cavalry as well as sharpshooters from the 18th

Iowa. They were soon corrected when hundreds of Confederate cavalry appeared

alongside them Cabell had ordered Crawford, who to this point had only

skirmished, to move all of his available men forward. Gibbons “immediately

ordered the men to fire, which was kept up for a few minutes only, but with

such effect as to check the enemy’s advance.” Among the men commended in

Gibbons’ report was First Sergeant Berry, a black officer who urged his men to

think of freedom and hold their place.[1]

Gibbons ordered his men 60 yards back. They fired a volley, but made another withdrawal when they saw the rest of the regiment in retreat. Crawford’s Confederates “moved rapidly and steadily forward, firing volley upon volley” at the black troops. Gibbons attempted to mount his horse. He tripped on his saber halfway up and the horse “became scared and dragged me about 5 yards.” His infantry left him behind and he was left alone against the on-rush of screaming Rebels. “I need not say I mounted quick and rode away quicker.”[2]